Self-employed financial resilience - September 2023

Foreword

Nathan Long, Senior Policy Analyst at Hargreaves Lansdown.

In January 2022, we launched the HL Savings & Resilience Barometer to understand the holistic financial resilience of households across the Nation. It was clear from this first edition that self-employed households differed significantly to those of employees. Notably lagging employees when it comes to later life saving and protecting their families in the event of death or ill health. However, these households tended to have a greater likelihood of investing to make more of their money. We asked Oxford Economics to conduct a deep dive on their financial resilience to take a more holistic look at their situation. It is a well-rehearsed narrative that the self-employed have given up on pension saving, particularly those who are basic rate taxpayers. However rather than a narrow pensions debate, we have noted that Lifetime ISAs could offer a more efficient and attractive way of saving for retirement for those people who will be basic rate taxpayers whilst working and also in retirement.

By contrast, those self-employed people who are higher rate taxpayers whilst working and basic rate in retirement, are likely to be well served by the tax relief system in pensions. They will often work with an accountant who can advise to make pension contributions.

This piece of work examines the wider financial resilience of the self-employed, before going on to consider two policy changes that could benefit their long-term savings resilience:

- Increasing the age that anyone can open and pay into a LISA until age 55.

- Reduce the penalty for any self-employed LISA holders accessing before age 60 to 20%. This acts to recover the government bonus but ensures those needing to withdraw early are not additionally penalised.

The results show that more than 1.2 million households with a basic rate tax paying self-employed earner could benefit from the proposed changes.

Hargreaves Lansdown believe these changes would be hugely beneficial because:

- They make the Lifetime ISA more relevant to the self-employed, 70% of whom missed out on the Lifetime ISA because they were too old when it launched in 2018.

- They make the Lifetime ISA increasingly attractive to self-employed workers who typically have variable cash flow and lack the confidence to put money away for the future without being able to access it.

There is an opportunity to tweak the rules of the Lifetime ISA to make what is currently a good retirement option for the self-employed a great one. This change would go some way to heading off the two-tier retirement landscape we are destined for, where those who have been employed their whole life have enough to get by, but those who have been self-employed are left struggling to meet the essentials. We call on the government to examine this simple change to provide a retirement saving product which is better suited to help 1.2 million households.

Andy Chamberlain – Director of Policy, IPSE (the Association of Independent Professionals and the Self-Employed).

One of the greatest strengths of the self-employed sector is its ability to offer much-needed flexibility to jobs markets and hirers. But in return, self-employed individuals are often met with inflexibility due to their employment status, including in financial products.

The self-employed have cause to maintain a greater level of financial liquidity to help them manage cycles in demand for their services, and to guard against threats such as late payment, non-payment, and unplanned expenditure.

With this in mind, the self-employed can be more reluctant to put money out of reach until they retire – especially not without the added incentive of additional contributions by an employer, and from the perspective of lower rate taxpayers, comparatively greater tax relief. But this only delays financial detriment until later life.

As the UK’s only not-for-profit organisation dedicated exclusively to the self-employed, IPSE has long called for savings products to be better tailored to the realities of being your own boss, the realities facing 4.3 million people today, and likely more in future.

That’s why IPSE is backing Hargreaves Lansdown’s recommendations in this report to extend the Lifetime ISA, which offers a unique opportunity to transform the savings landscape for the self-employed.

Executive summary

In 2018, the government introduced the Lifetime Individual Savings Account (Lifetime ISA) which provides an alternative tool to help individuals save for retirement. A Lifetime ISA can offer a more tax-efficient retirement saving option for basic rate taxpayers, contributions are made after tax and receive a government bonus but then withdrawing funds is not taxed. In comparison, contributions to a pension are made before tax and on withdrawal, 25% of a pension is tax-free while the remainder is taxed as income.

In contrast to employees who typically rely on employer-sponsored retirement plans, with an employer contribution, the self-employed must take greater initiative to establish their own retirement funds. In this endeavour, the Lifetime ISA can provide them with an attractive alternative tool. To bolster the adoption of Lifetime ISAs for the self-employed, Hargreaves Lansdown (HL) is currently advocating two policy changes:

- Enabling those aged between 40 and 55 to open an account and allow bonuses on contributions until age 55: Just over 1.5 million self-employed workers between this age were unable to open a Lifetime ISA when they were introduced. Enabling these individuals to open an account will provide them with an alternative financial tool to utilise for retirement planning.

- Reduction in the penalty to 20% for early access if self-employed: The proposal seeks to eliminate the current penalties for self-employed individuals seeking early access, sparing them from losing their personal savings and only forfeiting the government bonus. This can be expected to widen the appeal of this product to the self-employed as they often contend with a more precarious employment landscape, necessitating increased access to funds for unforeseen circumstances.

In this study, we use the data that underpins HL’s Savings and Financial Resilience Barometer to illustrate why these policy changes could be justified given the current financial position of the self-employed and to understand the potential scale of the intervention given the number of households that might be affected. Our key findings are as follows:

- In 2022 Q4, self-employed led households1 had a lower average level of financial resilience compared to those led by an employee. Specifically, according to the Barometer, the former’s average score was 52.9, significantly lower than the latter (67.1). Inferior pension adequacy was one of the primary factors explaining this gap.

- Across household types, there is significant variation between their ‘plan for later life’ scores indicating differences in their expected financial resilience upon retirement. Notably, self-employed led households had an average pillar score of 46.1, nine points lower than the average for employee led households.

- Expanding access to the Lifetime ISA for households aged between 40 and 55 could affect 680,000 households with a self-employed worker who pays the basic rate of tax. Of this group, approximately two-thirds were households where the primary earner was self-employed.

- Further, the removal of the penalty could benefit 540,000 households aged between 18 and 39 with a self-employed worker who pays the basic rate of tax. 400,000 of these households are self-employed led, while a further 140,000 households are where the self-employed is a secondary earner.

- Those paying the basic rate of tax are particularly vulnerable in terms of retirement financial resilience. Of this group, just 14.9% of self-employed led households aged between 18 and 39 are on track to have sufficient savings that would provide them with a moderate standard of living upon retirement2. This share is only slightly higher for those aged between 40 and 55 (21.9%). The scores for homeownership and other assets similarly underperform for these groups. This suggests a clear rationale for policymakers to seek to identify measures that would enable these households to plan for their retirement more effectively.

- These groups may feel the need to hold more funds in an accessible financial product as they show vulnerabilities to absorb a temporary financial shock, as measured by their surplus income indicator, and lack sick and redundancy pay. This supports the proposed policy change of reducing the penalty to access the Lifetime ISA early.

1 A self-employed led household is where the highest earner, also denoted as the primary earner, is self-employed. This represents an average of the possible secondary earners such as employee, self-employed, non-working and single-household. Similarly, an employee led household is where the highest earner is an employee and an average across all secondary earner options is used.

2 The value for pension indicator is based on the PLSA moderate standard of living.

Introduction

The self-employed play a crucial role in the UK workforce accounting for one in seven workers. The majority of self-employed workers believe they have greater flexibility, independence, and job satisfaction than they would if they were employees3. There are however financial disadvantages to self-employment. Indeed, regular income, job security, and benefits all ranked in the top five most popular responses when self-employed respondents were asked why they missed being an employee4.

Pensions and planning for later life can pose a specific challenge for self-employed individuals as they typically have lower pension participation, and even those who have taken out a pension do not benefit from significant employer contributions. While auto-enrolment has helped improve the outlook for employees, this did not cover the self-employed. Since its introduction in 2012, the gap between pension participation rates of employees and the self-employed with the same level of earnings has widened5. The self-employed are therefore at risk of being left behind, especially given the recent bout of high inflation that has increased the funds required to support retirement.

Pensions are not the only way to save for retirement. In 2018 the government introduced Lifetime Individual Savings Accounts (Lifetime ISA) which have steadily grown in popularity. While they were not directly designed for the self-employed, they provide an additional financial tool to save for retirement. Account holders can pay in up to £4,000 every tax year up to the age of 50 and, in return, the government will increase your contribution by 25%. Particularly for those paying the basic tax rate, Lifetime ISAs can provide account holders with a more tax-efficient way to save.

However, as the age at which someone can open a Lifetime ISA is limited to between 18 and 39, many savers are unable to access these accounts. Indeed, during the introduction of the scheme, there were 3.3 million6 self-employed individuals—70% of this group—who could not open one of these accounts. Furthermore, those who hold a Lifetime ISA are only able to access these savings from the age of 60. Any early withdrawal incurs a penalty wherein the government reclaims 25% of the savings' value, resulting in a repayment exceeding the government's initial contribution.

With a heightened policy focus on how to boost pension savings amongst the self-employed, expanding the access age to include those aged 40 to 55 and removing the withdrawal penalty to these accounts could broaden the appeal of these accounts boosting the number of self-employed using them. The aim of this report is twofold: firstly, to provide an overview of the self-employed, and secondly to examine their retirement plans using the barometer highlighting the financial resilience of the group. It will underscore the underperformance of those paying the basic rate of tax and how Lifetime ISAs can support this cohort’s retirement planning.

3'Understanding Self-Employment', BIS (2016)

4Self-Employment review (2016)

5Understanding pension saving among the self-employed, IFS (2023)

6Average of the 2018 quarterly LFS

The Self-Employed and their overall financial resilience

Financial resilience is best understood and assessed at the household rather than the individual level. This section begins by describing the characteristics of the self-employed but then explores their financial resilience in the context of their household.

Self-employed workers typically work for SME businesses and are concentrated in certain industries and occupations…

While the self-employed are a diverse segment of the labour force there are key sectors, occupations, and companies they work for7. This includes:

- The self-employed typically work for themselves or in small companies: the latest LFS showed 87.9% worked on their own or with partners and 12.1% worked in a company with employees. Of those working with employees, 77.2% reported working for a company which had 10 or fewer employees. As discussed in the July 2023 barometer release, organisational characteristics are correlated with household financial resilience as the share of financially resilient households in which the primary earner works for an SME is lower than for those working for large private sector companies or the public sector. Typically, larger organisations offer more support to their employees via better workplace benefits such as occupational pension contributions or enhanced sick pay.

- The construction industry accounts for the highest proportion of self-employed workers followed by other services and professional, scientific, and technical activities. According to the latest Labour Force Survey, these three sectors combined account for nearly half of all those self-employed.

- The self-employed predominantly work in four occupations: skilled trades occupations, professional occupations, associate professional occupations, and managers directors and senior officials account for three out of four of all self-employed workers.

- Two-thirds of the self-employed are males and 4 in 5 of them work full time. In contrast, a smaller portion of self-employed females work full-time, with just under half of them engaged in full-time work.

… and their average age is higher than that of employees

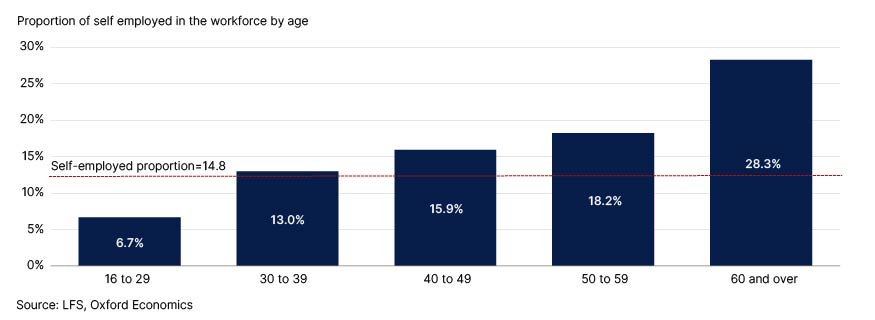

Upon the introduction of the Lifetime ISA in 2018, 3.3 million self-employed workers—70% of this group—were unable to open an account. Furthermore, those who are self-employed tend to be older than employees, with the average age of a self-employed worker at 47.6 nearly seven years older than employees8. This is important in the context of retirement planning for the self-employed as they are less likely to participate in pension schemes and do not benefit from employer pension contributions. This leads to the self-employed benefiting more from non-pension financial tools, such as the Lifetime ISA, that can support them in retirement. As shown in Fig. 1, over 80% of self-employed workers were aged 40 or above, excluding them from the Lifetime ISA scheme under the current legislation.

Fig. 1. Self-employed represent a higher proportion of older workers9

The composition of households with self-employed workers plays a role in their financial resilience.

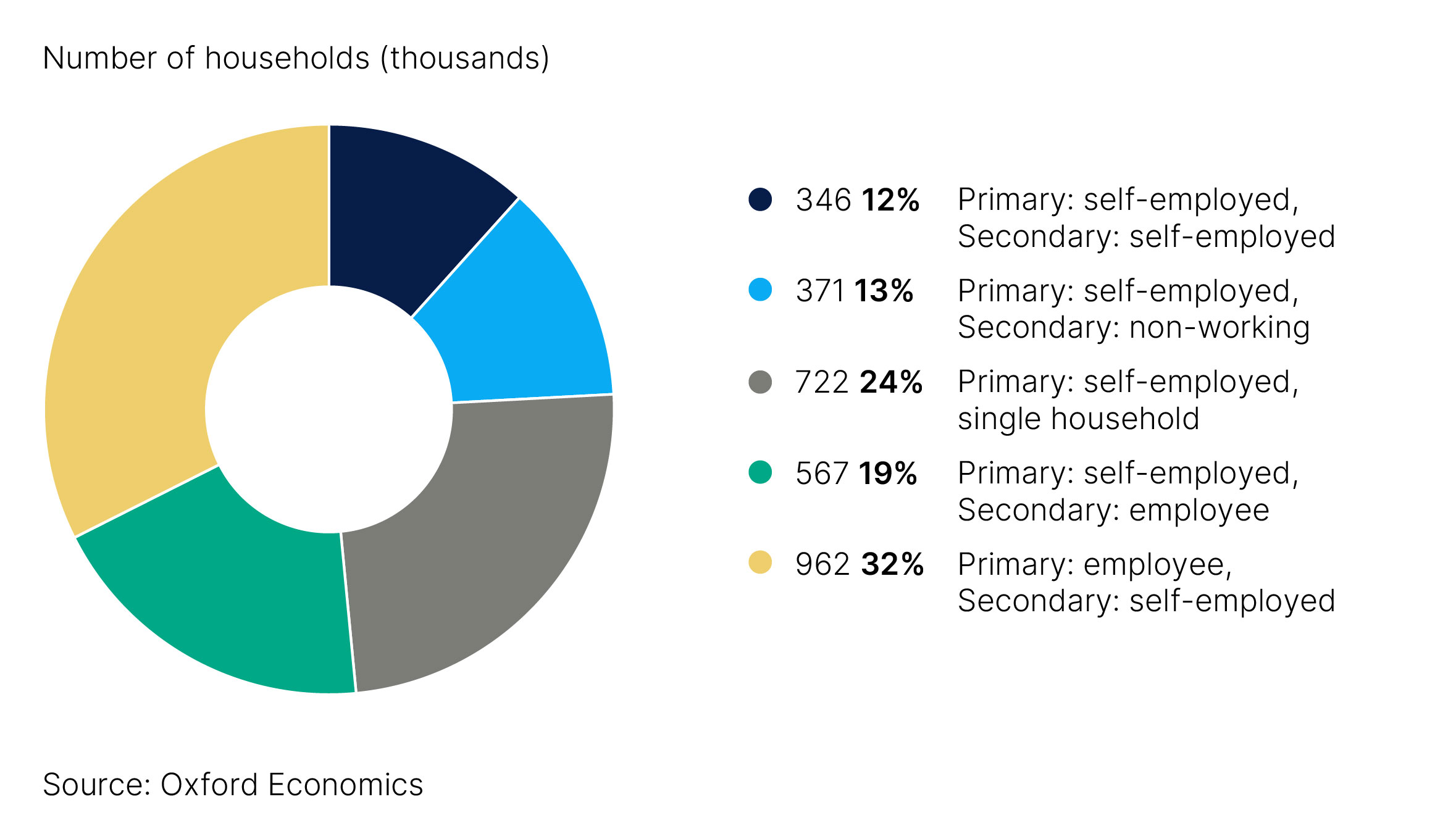

There are 3 million households where the primary earner10 or the secondary earner is categorised as self-employed. In just under half of these households, both primary earners are self-employed or the primary earner is self-employed and has no secondary earner (Fig. 2). On average, these households see fewer secondary earners working full-time compared to the primary earners. Additionally, there is a higher proportion of females who are the secondary earners indicating males tend to be the primary earners in these households.

Fig. 2. Number of households where at least one earner is self-employed11

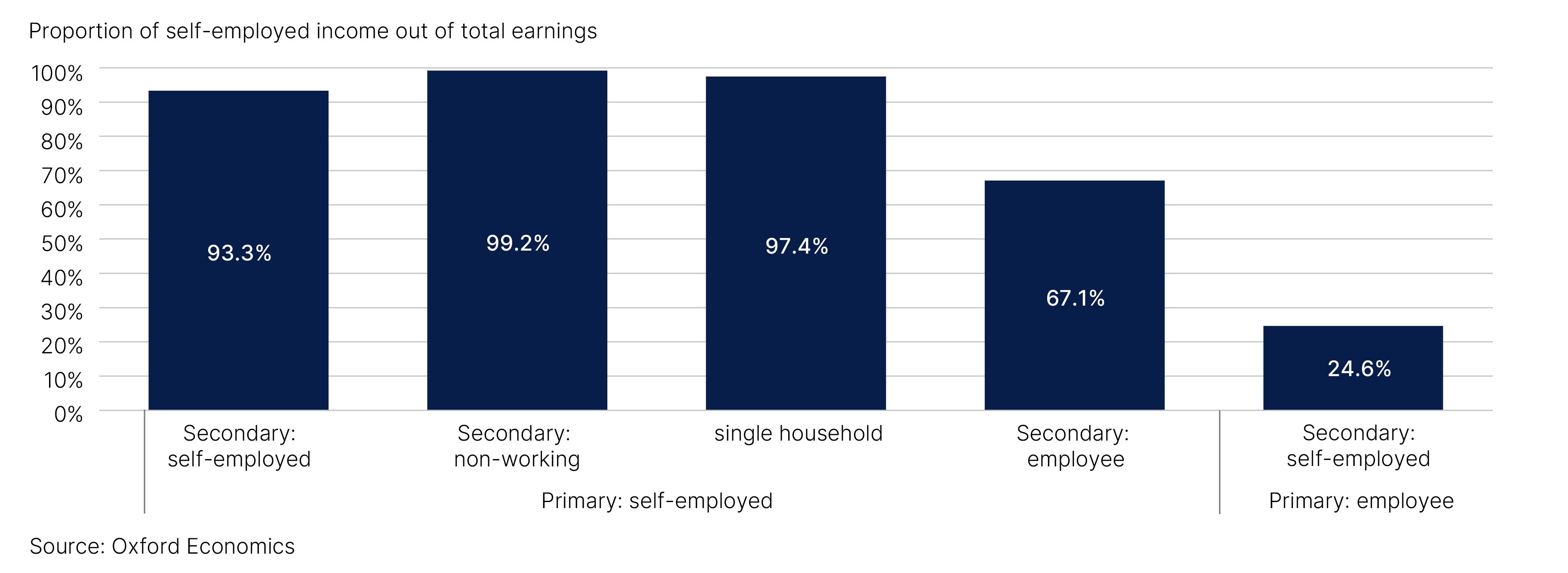

Households with a self-employed primary earner have a greater reliance on the self-employed worker to provide for the family. As shown in Fig. 3, this reliance decreases in households with an employee working with the proportion of earnings falling to 67.1% when the secondary earner is an employee and 24.6% for those where the primary earner is an employee and the secondary earner is self-employed.

Fig. 3. Limited reliance on the self-employed worker when they are the secondary earner in the household12

Households with self-employed workers have a lower financial resilience when compared to those who are employees.

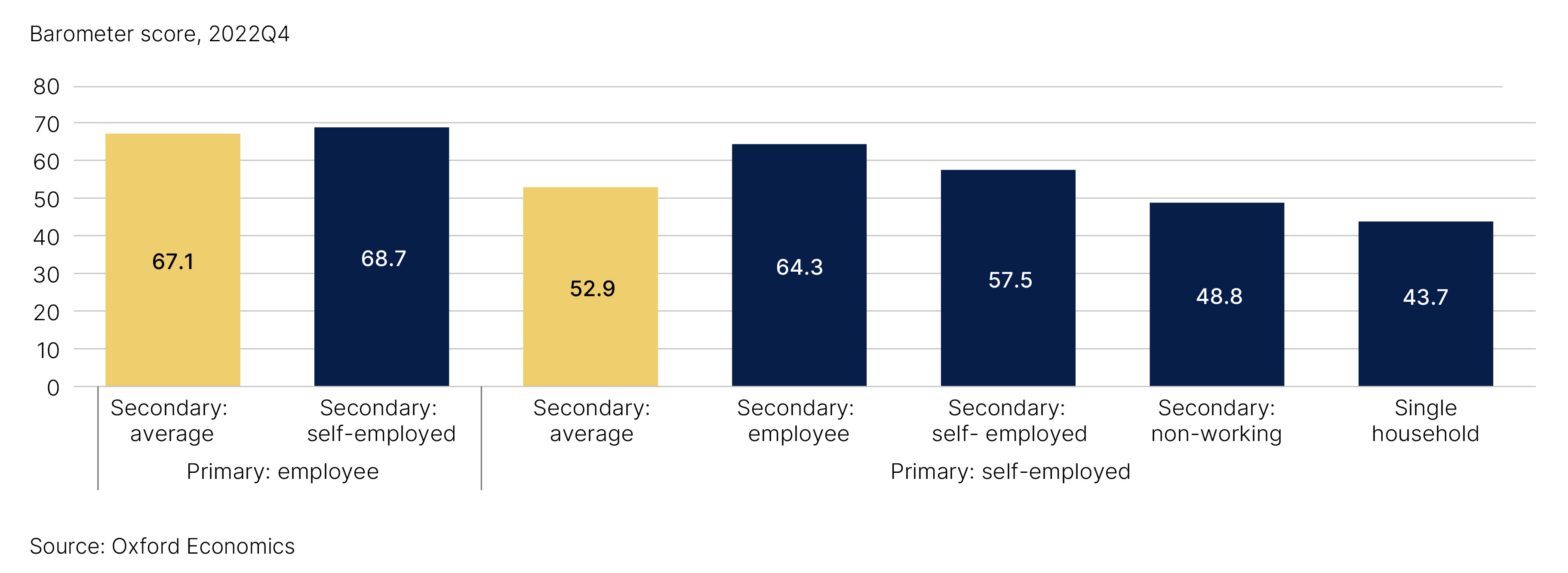

Using the indicators from the Barometer, we can provide detailed insights into the financial resilience of these household groups13. As shown in Fig. 4, there is a significant difference between the financial resilience of self-employed households and employee households. The gold bars display the average resilience score for an employee and self-employed led household. This represents an average of the possible secondary earners (employee, self-employed, non-working and single-household) to identify differences based on the employment status of the primary earner.

In 2022 Q4, self-employed led households scored 52.9 points overall significantly lower than the average score of an employee led household (67.1 points). This average however masks the differences between the types of self-employed households. Those self-employed led households that have two earners outperform those where there is only one self-employed worker. Furthermore, this chart highlights that those households that have an employee working as the primary or secondary earner are more financially resilient when compared to single earner households where there is a self-employed worker.

The difference compared to employee households has widened since the pandemic as it caused a unique set of challenges and uncertainties for the self-employed. Many individuals within this group experienced significant disruptions to their businesses and income streams as lockdowns, restrictions, and economic uncertainty took hold. For example, the construction industry, which accounts for one in six of the self-employed, has seen earnings growth underperform compared to the average. In 2022, construction wages were 9.7% higher than in 2019, this is lower than the average for the whole economy which was 14.6% higher than 201914. These factors have weighed on the improvement in their financial barometer score leading to only half the rise seen by households where the primary earner is an employee.

Fig. 4. Self-employed households have a lower financial resilience when compared to employee led households

Lack of workplace benefits hampering the financial resilience of self-employed households.

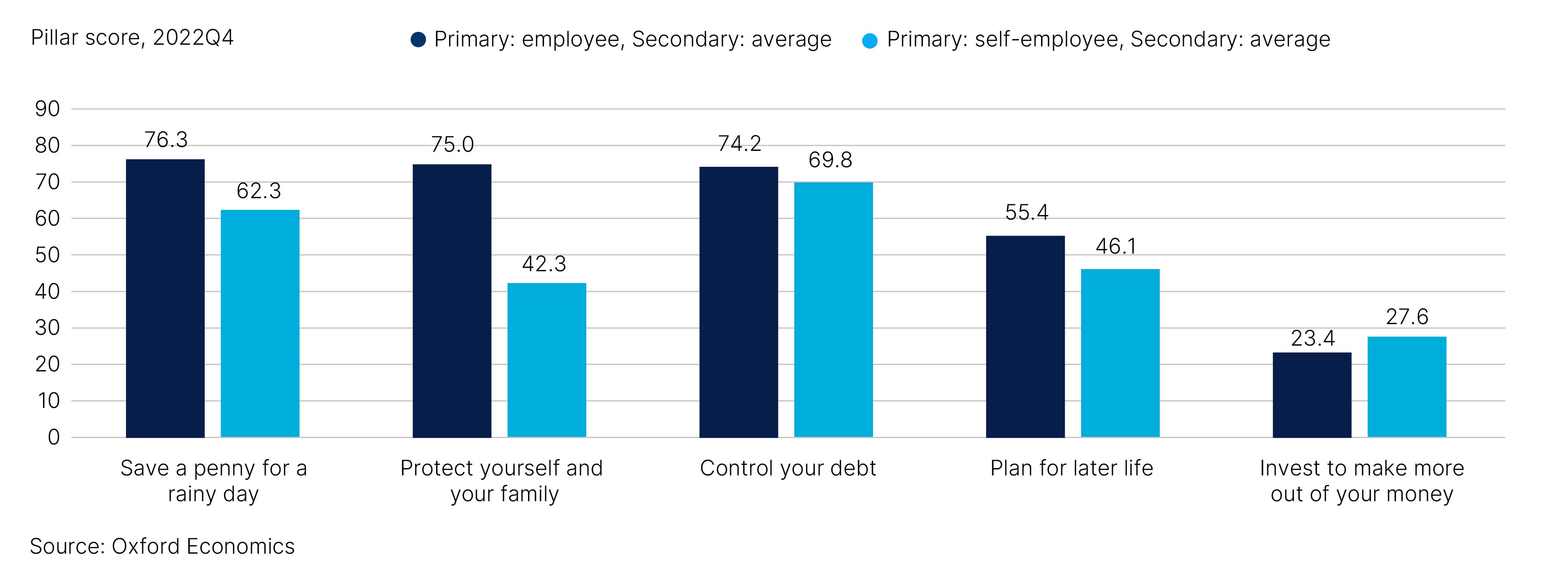

Differences in workplace benefits between employees and the self-employed typically underpin much of the gap between the self-employed and employee led households. Indeed, the gap in average scores in the ‘protect yourself and your family’ pillar is driven by the lack of access to sick pay while the absence of redundancy pay has a directionally similar effect on relative scores in the ‘save a penny for a rainy day’ pillar. Similarly, the pension value indicator shows the relative underperformance of self-employed led households contributing to their lower-than-average score in the ‘plan for later life’ pillar.

The lack of sick and redundancy pay as well as limited pension savings highlights the potential benefits of removing the penalty to access the Lifetime ISA early. With more limited employment protection, the self-employed may feel the need to hold more funds in an accessible financial product. By removing this barrier, the Lifetime ISA could become a more appealing tool for them to use.

Fig. 5. Gaps in pillar scores are driven by the lack of workplace benefits

7 2023Q1 LFS

8 Average of the 2018 quarterly LFS

9 Average of the 2018 quarterly LFS

10 As measured by the highest earner

11 Single households may have other adults or children in the household however, these are not the spouse, cohabitee or a civil partner of the primary earner.

12 The employment status is based on the current employment status of their main job. Households may have generated income from a second job or a previous job with a different employment status to that used for categorisation. Other sources of income households may have include benefits, earnings from investments and irregular earnings (for example inheritance and insurance pay-outs).

13 While the Barometer tracks the wealth of the self-employed over time, it does not capture any change in the composition of those who are self-employed. To incorporate these changes in composition, we have updated the barometer's household weights. More information on this can be found in the appendix.

14 Based on average weekly earnings by sector published by the ONS

Retirement resilience of the Self-Employed

Lifetime ISAs are known for their flexible savings options and government-backed bonuses, which provide an alternative to pensions for the self-employed to actively save for their retirement while capitalising on tax-efficient growth. This strategic approach not only aligns with self-employed people's disposition towards diversified assets but also addresses the unique challenges they face in securing a stable financial future post-career.

Retirement planning diverges between those who are self-employed and employees with the self-employed potentially more likely to utilise the Lifetime ISA.

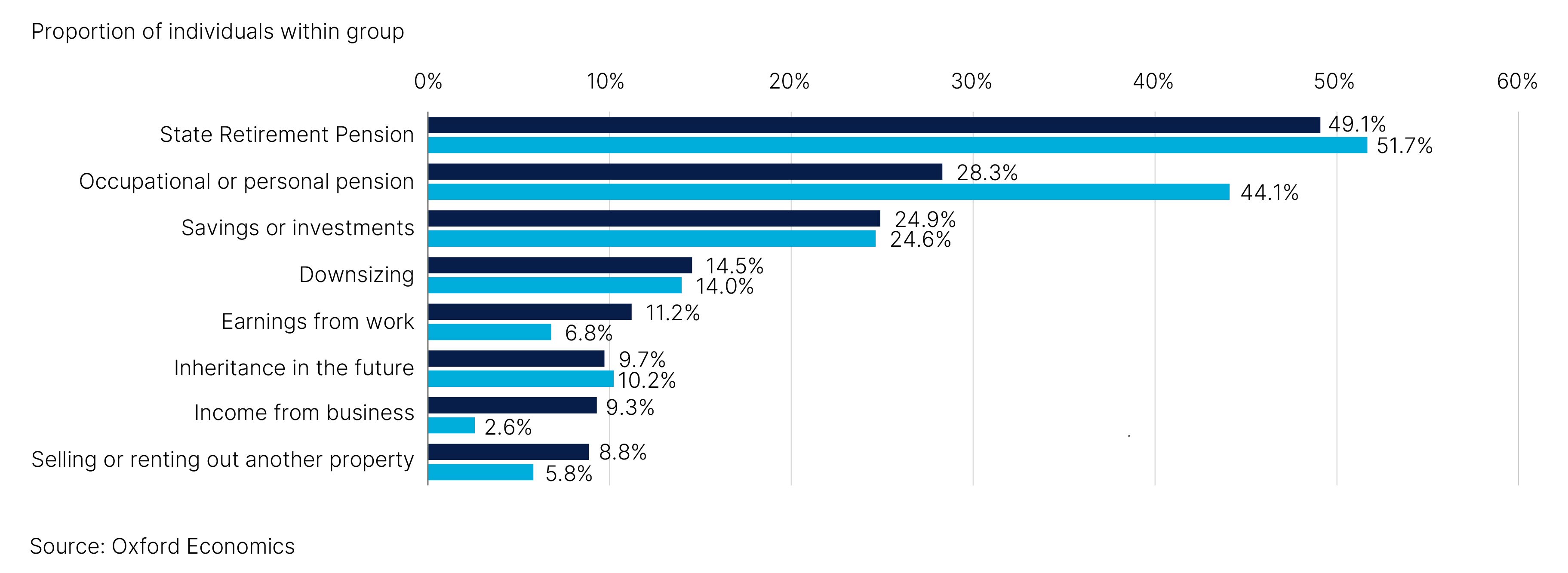

When asked, the self-employed indicated that they were expecting to use multiple sources of income to fund their retirement. This multifaceted approach underscores the unique strategies self-employed individuals adopt to secure their financial future post-career and the benefits an expansion of the Lifetime ISA could provide to them.

Unlike employees who typically rely on employer-sponsored retirement plans, the self-employed must take the initiative to establish their own retirement funds. In this endeavour, they are expecting to rely on their business as a source of income as well as selling or renting out property to supplement their retirement funds. Furthermore, self-employed individuals anticipate extending their working years, enabling them to accumulate more savings to ensure a stable retirement.

Fig. 6. Self-employed are more likely to use non-pension sources to provide income upon retirement.

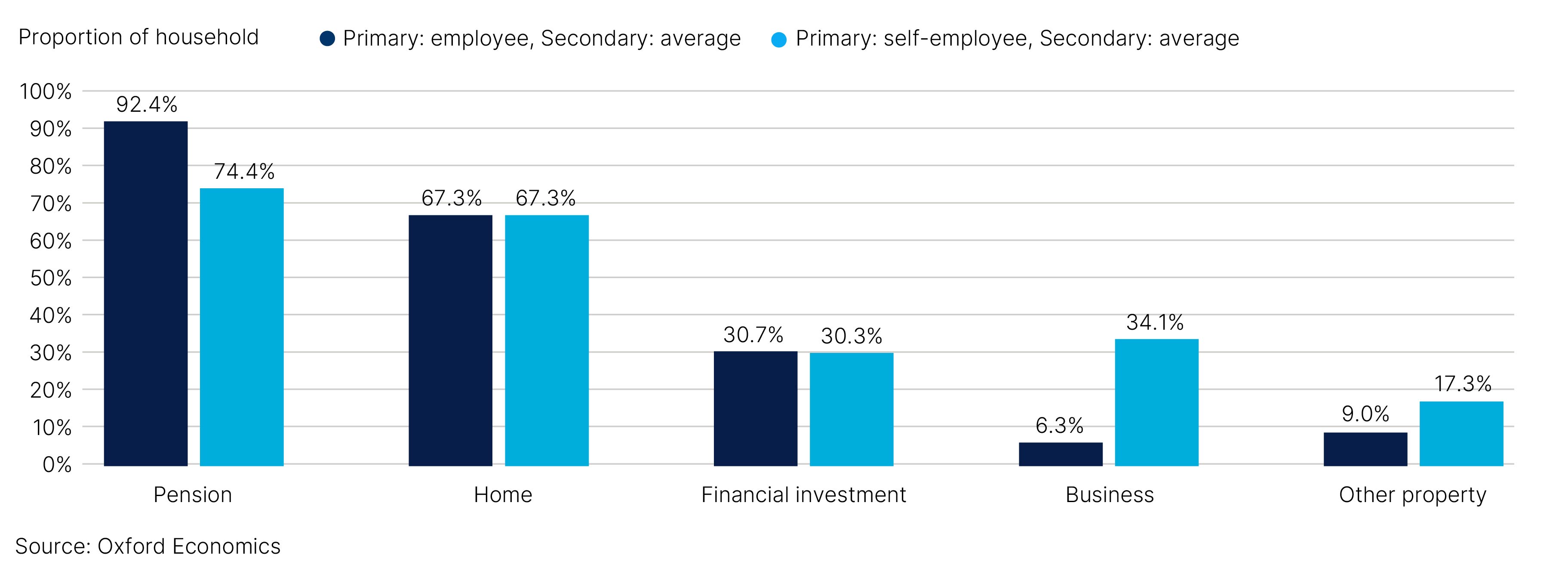

Fig. 7 confirms the retirement plans of self-employed individuals as they rely on a wider range of financial assets. While a significantly lower share of self-employed led households hold a pension, they are significantly more likely to have an equity share in a business and to own a property outside of their main home.

Fig. 7. Self-employed households are less likely to hold a pension, but more likely to own a business and other property.

As individuals age, they are more likely to have accumulated assets due to factors such as longer periods of work, savings, and investment growth. The indicators in this pillar take this into account when calculating their financial resilience scores by using age-specific thresholds. As a result, the barometer provides a more accurate gauge of their expected position in retirement. For more details on these thresholds see the methodology document15.

Self-employed households are less resilient than their employee counterparts highlighting the need to focus policy on supporting them such as an expansion to the Lifetime ISA.

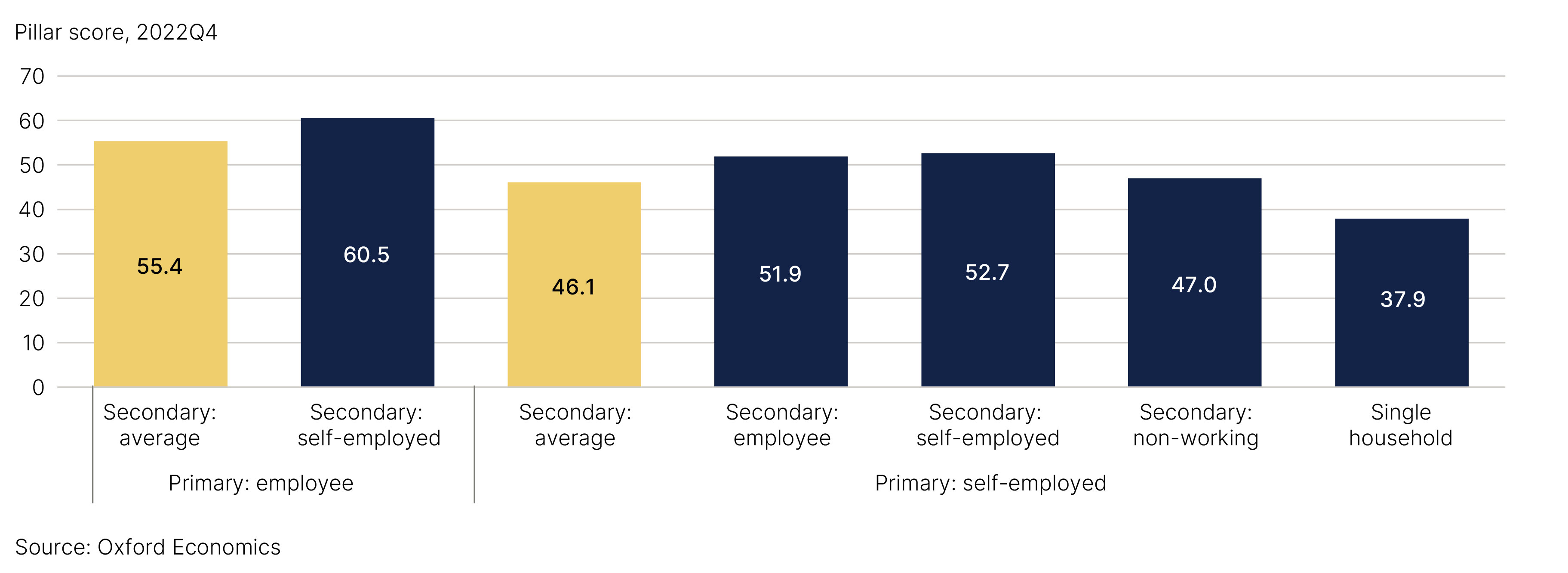

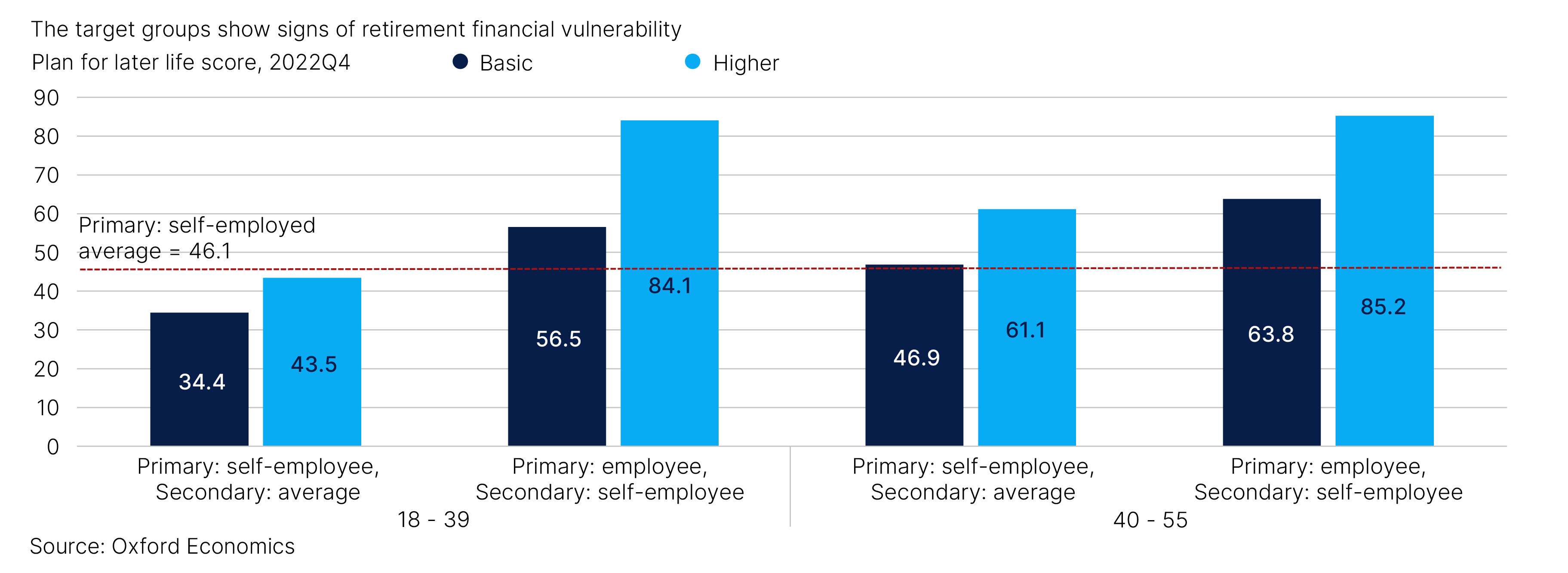

As shown in Fig. 8, the differences in the ‘plan for later life’ pillar underscore the unique challenges faced by the self-employed in terms of retirement planning and long-term financial security. The average pillar score of the self-employed led households was 46.1 points, just over nine points less than the average of the employee led households.

Across household types, there is variation between their scores. Notably, single self-employed households show significant signs of vulnerability as they score over 8 points less than the self-employed average and less than the other groups. In contrast, households where the self-employed is a secondary earner have a higher degree of financial resilience. This suggests that these households are potentially leveraging the financial resilience provided by the employee.

Fig. 8. Plan for later life indicator scores indicate the self-employed are lagging

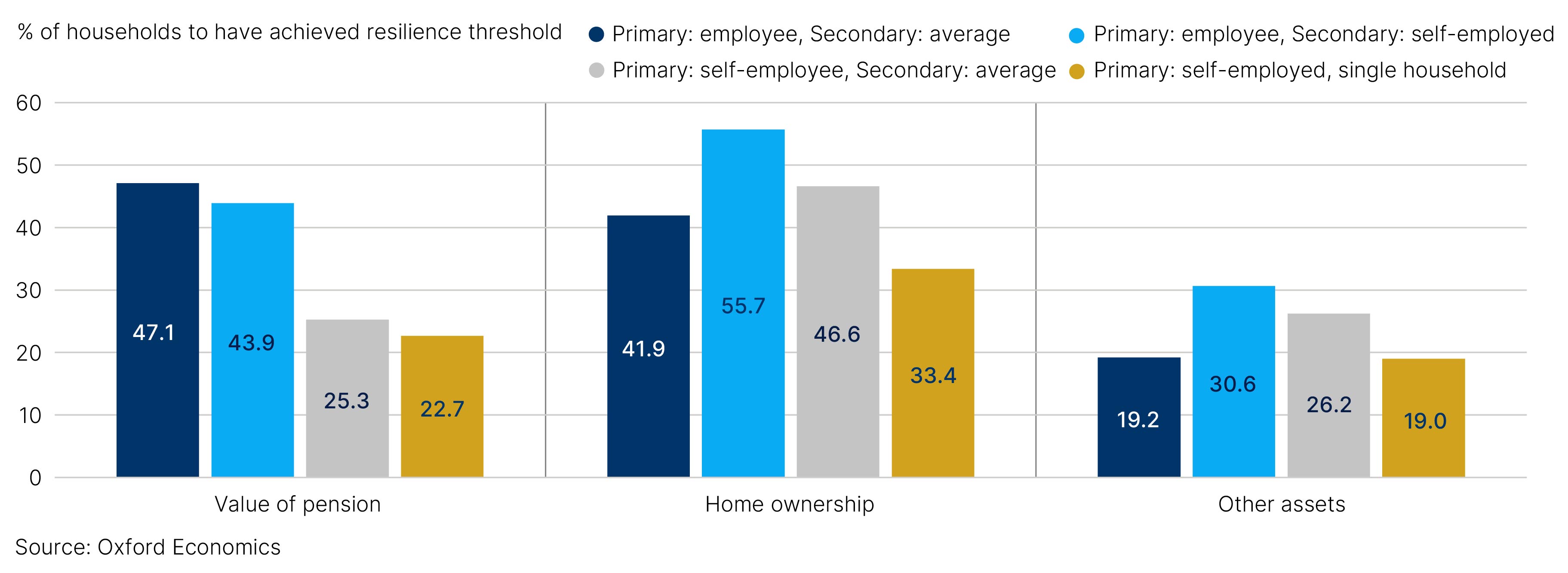

Self-employed make use of non-pension tools to save for retirement highlighting the suitability of Lifetime ISAs.

Our data show that while holding lower valued pensions, self-employed led households typically hold more wealth in their homes and other financial assets meaning that a higher proportion of these households reach the specified resilience threshold for these indicators in the Barometer.

Among self-employed households, single self-employed households significantly underperform in both the value of pension and homeownership indicators while there is less of a gap with other assets. This suggests that these households may benefit more from an expansion of a Lifetime ISA as they are more likely to have their retirement funds in assets that are not pensions or their home. Households where the self-employed worker is the secondary earner (the primary earner is an employee) are less likely to be financially vulnerable with a high proportion of households reaching the resilience thresholds across all three indicators.

Fig. 9. Largest gaps between households seen in value for pension and home ownership

15 Savings and resilience comparison tool

Benefits of the Lifetime ISA reforms for the Self-Employed

Removing the penalty for early withdrawal and increasing access to the Lifetime ISA could help improve the adoption of this tool by the self-employed.

A Lifetime ISA can offer a more tax-efficient way to save for retirement for basic rate taxpayers. This is because with a Lifetime ISA, contributions are made after tax, but money is not taxable when it is withdrawn. In comparison, pension contributions are made before tax is deducted and while 25% of a pension is tax-free, the rest is taxable as income. Those who hold a Lifetime ISA are only able to access these savings from the age of 60 without incurring a penalty cost. Currently, any early withdrawal incurs a penalty wherein the government reclaims 25% of the savings' value, resulting in a repayment exceeding the government's initial contribution. As discussed above, a Lifetime ISA is only available to those who are between the ages of 18 and 39.

By facilitating the broader adoption of Lifetime ISAs, policymakers and financial institutions can offer self-employed individuals a valuable financial tool to bolster their retirement outlook. Hargreaves Lansdown is currently advocating two policy changes to achieve this goal:

- Enabling those aged between 40 and 55 to open an account and allow bonuses on contributions until age 55. Just over 1.8 million self-employed workers between this age were unable to open a Lifetime ISA when they were set up. Enabling these individuals to open an account will provide them with an alternative financial tool to utilise for retirement planning.

- Reduction in the penalty to 20% for early access if self-employed. Under this proposal, the penalty is effectively removed for self-employed individuals as they only stand to lose the government bonus and not any of their savings. This could benefit all currently eligible self-employed individuals, as well as those aged 40 - 55, giving them greater flexibility in managing their financial affairs. This is important as they often contend with a more precarious employment landscape, necessitating increased access to funds for unforeseen circumstances.

Half of self-employed households aged between 40 and 55 could benefit from the expansion of the Lifetime ISA scheme.

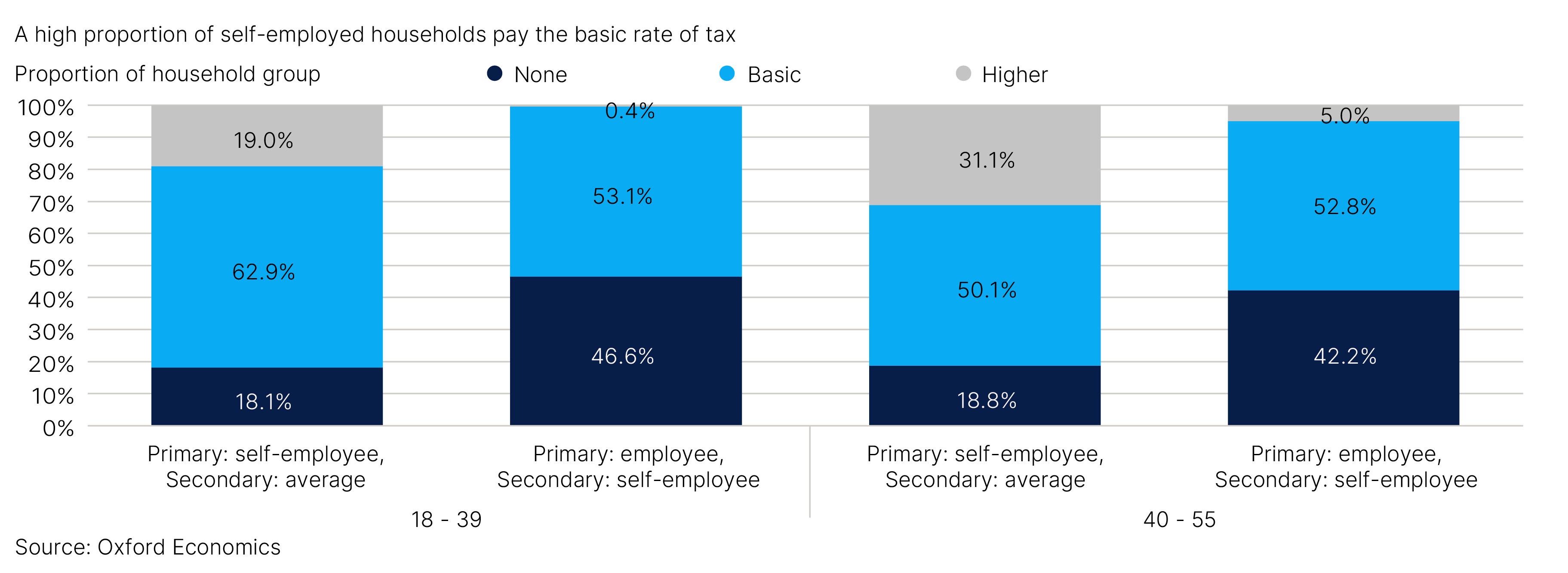

Those who are paying the basic rate of tax stand to gain the most from opening a Lifetime ISA. We have used the dataset underpinning the Barometer to categorise households with self-employed workers according to their income tax rate status: zero, basic rate, and higher rate (Fig. 10). For households with two self-employed workers, status has been assigned based on the primary earner. Where the primary earner is an employee, the household is assigned based on the tax rate paid by the self-employed secondary earner. Households where the primary earner is an employee, and the secondary earner is self-employed are presented distinctly in the following section. As previously discussed, this group are typically relatively financially resilient in the context of retirement planning. To avoid distortions, therefore, we think it is more instructive to separate this group in our analysis.

As shown in Fig. 10, this policy change could affect a substantial proportion of households containing self-employed workers aged between 40 and 55. We estimate it would affect 450,000 households where the primary earner is self-employed and pay a basic rate of tax. An additional 230,000 household would benefit when the secondary earner is self-employed and pay a basic rate of tax.

In addition to broadening the age group who can access these accounts, the removal of the penalty for early fund withdrawal could also benefit self-employed individuals who pay taxes at the basic rate and currently possess the eligibility to establish an account. This change aims to encourage those who might otherwise be deterred due to the existing penalty. Over half of these households in each group are paying the basic rate of tax and would benefit from opening a Lifetime ISA. Currently, the removal of the penalty will benefit 400,000 households who pay a basic rate of tax and the primary earner is self-employed with a further 140,000 households expected to benefit where the secondary earner is self-employed.

Fig. 10. A high proportion of self-employed households pay the basic rate of tax

Those paying the basic rate of tax underperform compared to those paying higher taxes

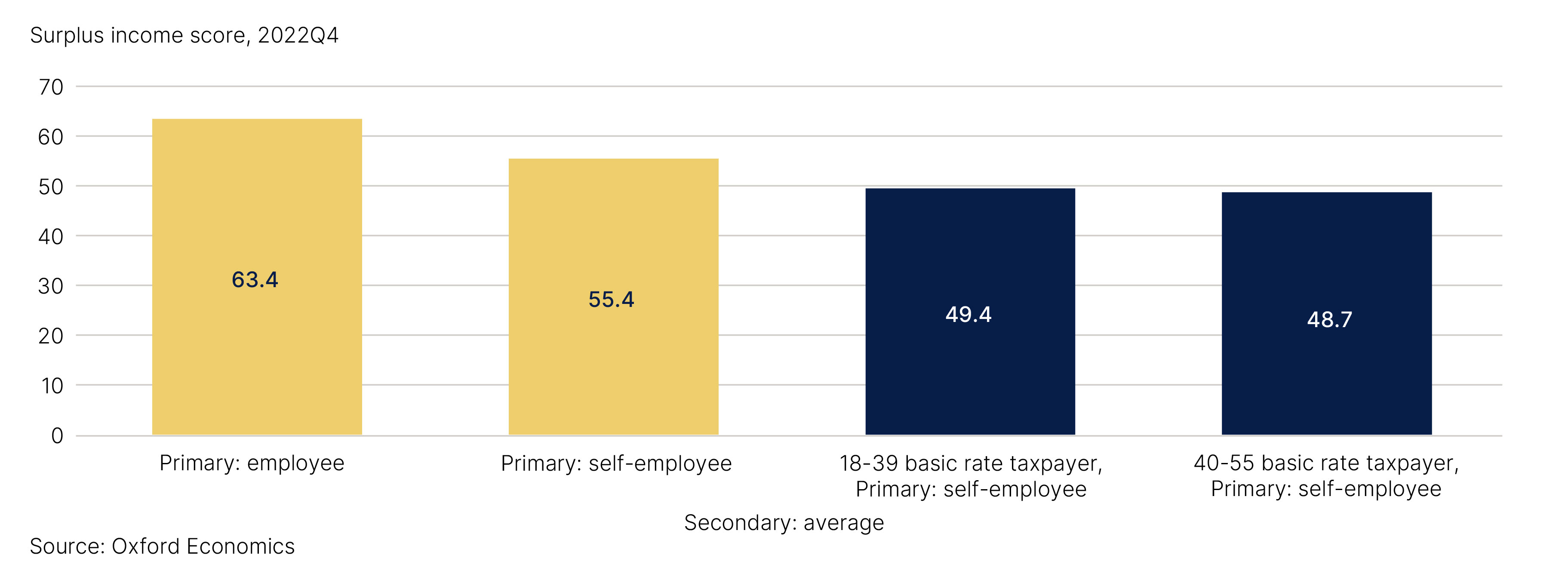

The gap in financial resilience across tax brackets is illustrated in Fig. 11. Notably, households paying the basic rate of tax trail behind those in the higher tax bracket with those currently eligible significantly below this average. The difference is more pronounced where the primary earner is an employee however, this group outperform the self-employed led household average.

Fig. 11. The target groups show signs of retirement financial vulnerability

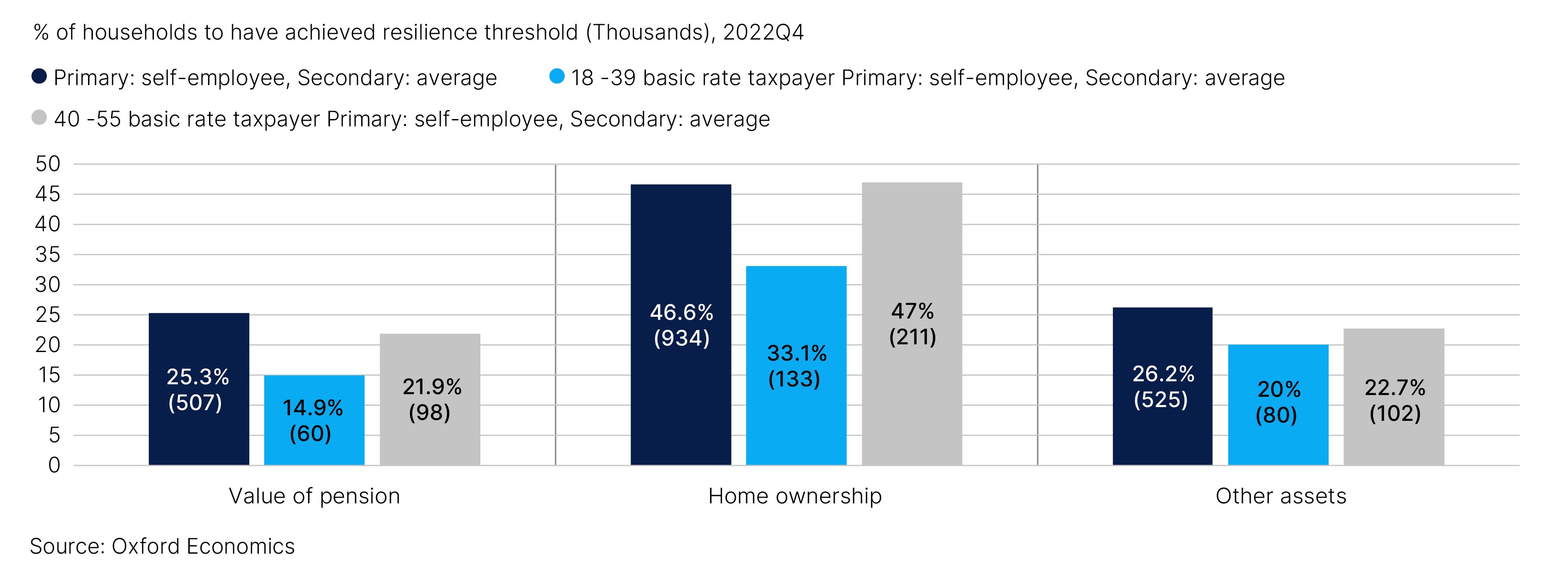

Fig. 12 focuses on those households that pay the basic rate of tax and where the primary earner is self-employed. This cohort generally suffers from lower levels of financial resilience as measured by the Barometer. This trend is particularly acute among households where the primary earner is younger (aged 18 -39) i.e., those who are currently eligible for a Lifetime ISA.

The data paints a concerning picture. Even adjusting for their age, just one-third of this cohort have reached adequate thresholds for wealth accumulation in terms of their own home and even less for other non-pension assets. This share drops even further to just 14.9% for the pension value indicator which measures the proportion of households who are on track to save enough for a moderate standard of living on retirement16. Although these shares are higher for those households where the primary earner is aged 40 to 55, they still trail the self-employed led household average in two of the three indicators, highlighting their vulnerability.

Fig. 12. Few of the intended target groups have reached the resilience threshold

Removing the penalty could make the product more appealing to the target group.

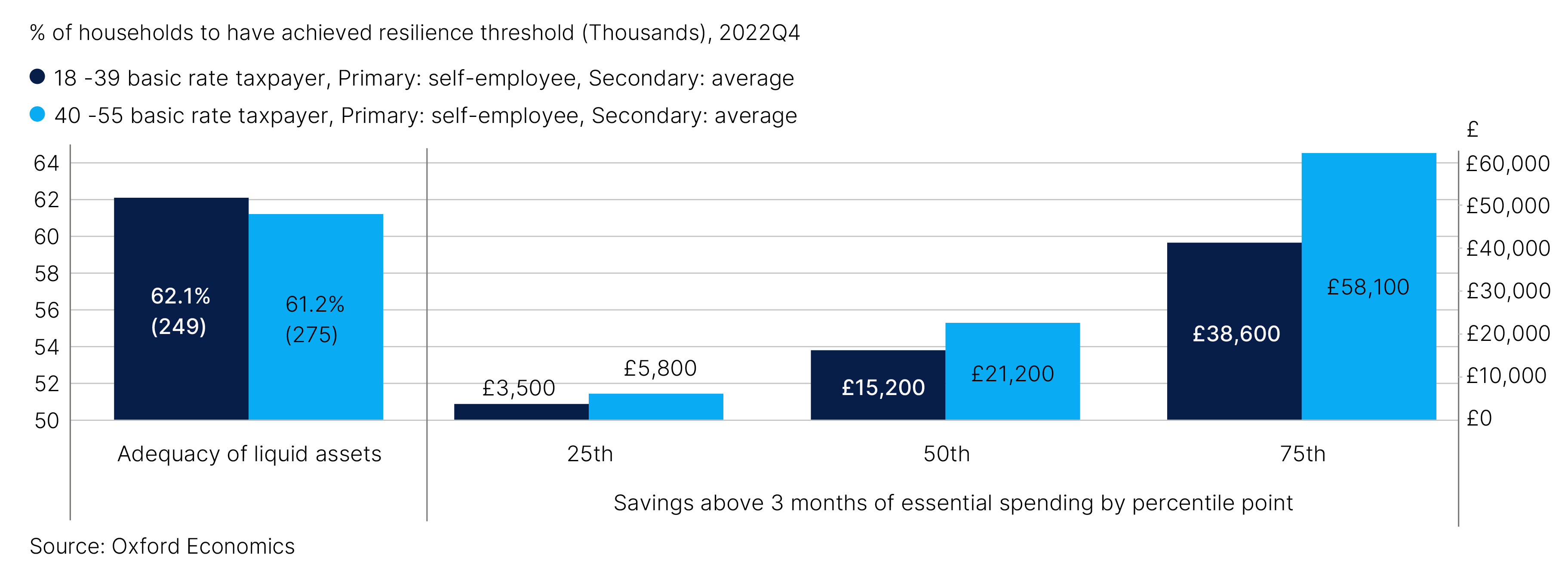

The ability of these households to put money into these accounts also needs to be considered. By evaluating both their liquid assets and surplus income indicators, we gain valuable insights into potential constraints that might impede their ability to do this. Among the target group, just under two-thirds possess sufficient liquid assets to cover an unexpected large expense of hit to their income. Among those who meet our resilience threshold, many hold a large amount of savings above three months of essential spending. Indeed, Fig. 13 shows that the 25th percentile of those aged 18-39 have £3,500 in liquid assets above 3 months of essential spending and those aged 40-55 have £5,800 in liquid assets above 3 months of essential spending.

Fig. 13. Many households could potentially put funds into Lifetime ISA

As shown in Fig. 14, households where the primary earner is a basic rate taxpayer have relatively lower levels of surplus income i.e., household income less total expenditure. Moreover, given the self-employed’s lack of access to sick and redundancy pay, it is perhaps unsurprising that many may be deterred from locking their money away into a Lifetime ISA. This strengthens the argument to reduce the withdrawal penalty. This would mean that these individuals will be able to access the funds in their account during times of need without incurring a damaging financial penalty. This may lead to the self-employed moving some of their savings that are currently in easy-to-access accounts into the Lifetime ISA. This would provide them with higher returns on their savings for retirement as well as the ability to access them if needed.

Fig. 14. Household where the primary self-employed earner is a basic rate taxpayer have relatively lower levels of surplus income

Concluding comments

Our analysis demonstrates that self-employed households are, on average, more financially vulnerable compared to employee led households. This is primarily underpinned by the limited pension savings they hold, with only one in four having the required savings to provide a moderate standard of living in retirement, half of the figure seen in employee led households. While this is somewhat offset by higher levels of wealth held in other asset forms (including their own home), the Barometer data suggests that this group is currently significantly less likely to be adequately prepared for the loss of income suffered in retirement.

Focusing on the self-employed who stand to benefit most from the Lifetime ISA expansion – those who pay the basic rate of tax – the analysis paints a more concerning picture. These households are more financially vulnerable than the average self-employed led household, which already underperforms relative to the average employee led household. Among those where the primary earner is aged 40 to 55, just over one-fifth have reached the adequate thresholds for their pension value and other assets, while half have reached the homeownership resilience threshold.

The situation is even more concerning for households where the primary earner is aged 18-39. Only 14.9% have reached the adequate threshold for the value of pension and wealth accumulation in terms of either their own home or other non-pension assets also underperforming.

Just under two-thirds of the target group possess sufficient liquid assets meaning they could move any excess money from their easy access accounts to the Lifetime ISA. However, the surplus income score falls short in comparison to both the averages for households led by employees and those led by self-employed individuals. When you factor in the absence of sick and redundancy pay for self-employed individuals, it could dissuade many households from committing their funds to a Lifetime ISA in its current form.

This data provides a rationale for policymakers to act by designing measures that will support the long-term planning and saving behaviour of this group. The two options explored in this research removing the early withdrawal penalty on the Lifetime ISA and reducing the withdrawal penalty to 20% would both support his end.

16 The value for pension indicator is based on the PLSA moderate standard of living

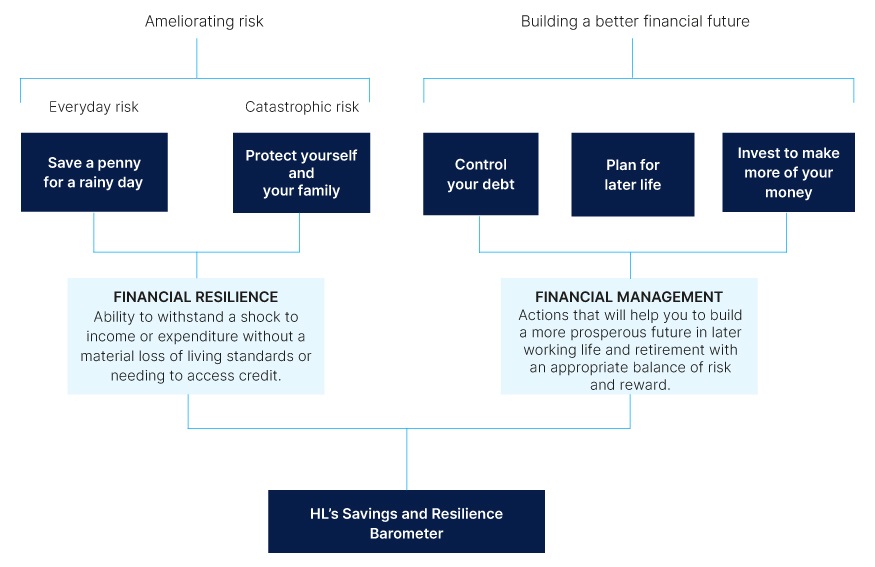

About the barometer

The savings and financial resilience barometer is an index measure designed and produced by Oxford Economics. It is based around Hargreaves Lansdown’s five building blocks for financial resilience depicted in Fig. 14. The aim of the barometer is to provide a holistic measure of the state of the nation’s finances, monitoring to what extent households are prudently balancing current and future demands whilst guarding against alternative types of risk.

Fig. 15. Savings and Resilience Barometer: conceptual structure

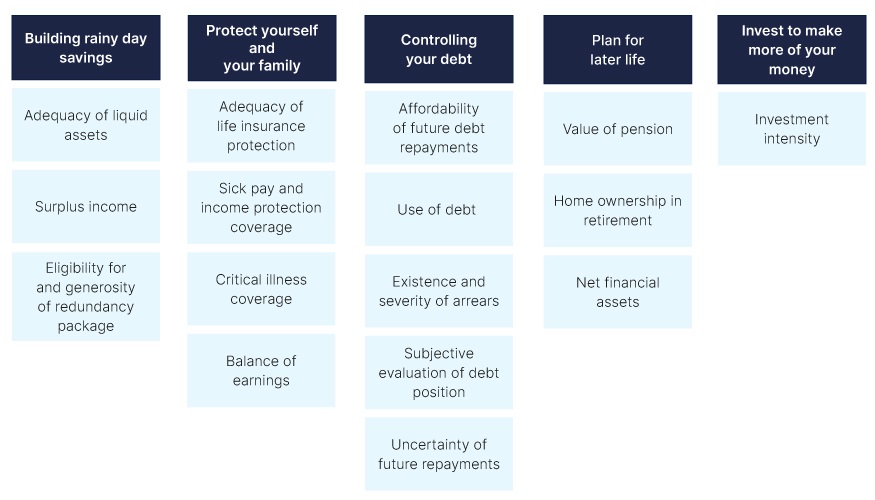

In collaboration with Hargreaves Lansdown, Oxford Economics mapped each of these pillars to a list of 16 individual indicators (Fig. 15). For the July 2023 release, there has been a methodological change to the (formally known) ‘Protect your family pillar’. We now include households who do not have dependants for critical illness, sick pay and balance of earnings. Life insurance coverage remains only for households with dependants. This updated pillar will now be called ‘Protect yourself and your family’. A single household now takes the value zero for the balance of earnings indicator. The Sick pay and critical illness indicator will be based on household characteristics.

The data underpinning the indicators is sourced from a household panel dataset for a representative group of British households developed by linking together official datasets. The Wealth and Assets Survey (WAS), published by the ONS, has been used as the core dataset due to the breadth of financial data available in the survey. This source does not include every variable required to measure the factors and the latest survey only extends as far as 2020 Q1. Therefore, we have used a range of methods including econometric analysis to build upon the core dataset using data from the Financial Lives Survey (FLS), Living Costs and Food Survey (LCFS) and the Labour Force Survey (LFS).

For each indicator, the data were used to create an index value on a scale of between zero and 100 for households in the panel. In each case, a score of 100 was assigned to households who had reached a specified resilience threshold e.g., holding liquid assets equivalent to at least three months of essential expenditure. Households whose savings are sufficient to cover more than three months of spending are, therefore, not rewarded for this additional level of security. Such a design is appropriate to capture the concept of resilience and the intrinsic trade-offs involved in financial management. Threshold values are defined concerning benchmark recommendations where available and, where not, using the statistical distribution of values within the dataset and the judgement of the research working group.

Fig. 16. Savings and Resilience Barometer: Barometer Indicators

To bring the dataset up to date, values have been extrapolated through to 2022 Q4 using a wide range of macroeconomic and survey data and different modelling techniques. A much more detailed description of the approach can be found in the methodology report available on the project’s landing page17. Finally, current and future values are projected based on Oxford Economics’ baseline forecast for the UK economy from its Global Economic Model (GEM).

Reweighting

This study is underpinned by the indicators from the Hargreaves Lansdown Barometer. While the barometer tracks the wealth of the self-employed over time, it does not capture any change in the composition of those who are self-employed. To ensure that our findings are a reliable depiction of those who are currently self-employed, we adjusted the Barometer weights based on the Labour Force Survey (LFS) and Family Resources Survey (FRS) to create a unique set of weights. Notably, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), the composition of self-employed workers in the UK changed markedly during the pandemic as workers were incentivised to switch their employment status due to the furlough scheme. Moreover, the reclassification of employee status by workers during this period was particularly concentrated among business directors and partners, and those in high-skilled occupations18. This implies that failing to correct for this recent shift may bias results. While the LFS is the most reliable source for providing information for the self-employed on an individual basis, it does not capture information at the household level. We therefore supplement the analysis by incorporating the latest FRS to accurately measure the employment status (employee, self-employed, non-working, or single household) of the primary and secondary earner in the household. The weights will therefore reflect the latest occupational distribution and the employment status of the primary and secondary earner.

To do this, the LFS and FRS have been used to calculate an adjustment factor that is applied to the current household weights ensuring the Barometer dataset aligns with these sources. Using a rake and scale methodology we created an adjustment factor that when applied to the WAS ensures we match both the LFS and FRS employment statistics as closely as possible. Given the Barometer dataset is based on households, we have excluded those outside of these two main earners in this analysis. This is expected to have a limited impact as the combined primary and secondary earners account for just under 96% of the self-employed labour market19. The tables below show the occupational distribution of self-employed people in the Barometer dataset before and after applying our weights and compare this to the LFS and FRS distribution.

Fig. 17. Occupational distribution adjustment using the LFS

Score range |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupation | LFS 202320 | WAS excluding adjustment factor |

WAS including adjustment factor |

|||

| Managers, directors and senior officials | 13.7% | 12.3% | 13.6% | |||

| Professional occupations | 17.8% | 14.9% | 17.9% | |||

| Associate professional occupations | 17.4% | 15.5% | 17.4% | |||

| Administrative and secretarial occupations | 3.3% | 3.7% | 3.2% | |||

| Skilled trades occupations | 23.8% | 26.0% | 23.9% | |||

| Caring, leisure and other service occupations | 7.9% | 8.9% | 8.0% | |||

| Sales and customer service occupations | 1.5% | 1.5% | 1.5% | |||

| Process, plant and machine operatives | 9.0% | 10.3% | 9.0% | |||

| Elementary occupations | 5.5% | 6.7% | 5.5% | |||

Fig. 18. Primary and secondary earner distribution adjustment using the FRS (thousands)

Score range |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary and secondary earner | FRS 2021/22 (thousands) |

WAS excluding adjustment factor (thousands) |

WAS including adjustment factor (thousands) |

|||

| Primary: self-employed, Secondary: self-employed | 352 | 280 | 346 | |||

| Primary: self-employed, Secondary: non-working | 365 | 366 | 371 | |||

| Primary: self-employed, single household | 731 | 747 | 722 | |||

| Primary: self-employed, Secondary: employee | 556 | 637 | 567 | |||

| Primary: employee, Secondary: self-employed | 951 | 871 | 962 | |||

17 https://www.hl.co.uk/features/5-to-thrive/savings-and-resilience-comparison-tool

18 Understanding changes in self-employment

19 Based on the FRS 2021/22

20 The average of 2023Q1 to 2022Q2 is used for the LFS as the data was non-seasonally adjusted

ABOUT OXFORD ECONOMICS

Oxford Economics was founded in 1981 as a commercial venture with Oxford University’s business college to provide economic forecasting and modelling to UK companies and financial institutions expanding abroad. Since then, we have become one of the world’s foremost independent global advisory firms, providing reports, forecasts and analytical tools on more than 200 countries, 100 industries, and 8,000 cities and regions. Our best-in-class global economic and industry models and analytical tools give us an unparalleled ability to forecast external market trends and assess their economic, social and business impact.

Headquartered in Oxford, England, with regional centres in New York, London, Frankfurt, and Singapore, Oxford Economics has offices across the globe in Belfast, Boston, Cape Town, Chicago, Dubai, Dublin, Hong Kong, Los Angeles, Mexico City, Milan, Paris, Philadelphia, Stockholm, Sydney, Tokyo, and Toronto. We employ 600 staff, including more than 350 professional economists, industry experts, and business editors—one of the largest teams of macroeconomists and thought leadership specialists. Our global team is highly skilled in a full range of research techniques and thought leadership capabilities from econometric modelling, scenario framing, and economic impact analysis to market surveys, case studies, expert panels, and web analytics.

Oxford Economics is a key adviser to corporate, financial and government decision-makers and thought leaders. Our worldwide client base now comprises over 2,000 international organisations, including leading multinational companies and financial institutions; key government bodies and trade associations; and top universities, consultancies, and think tanks.

September 2023

All data shown in tables and charts are Oxford Economics’ own data, except where otherwise stated and cited in footnotes, and are copyright © Oxford Economics Ltd.

The modelling and results presented here are based on information provided by third parties, upon which Oxford Economics has relied in producing its report and forecasts in good faith. Any subsequent revision or update of those data will affect the assessments and projections shown.

To discuss the report further please contact:

Henry Worthington:hworthington@oxfordeconomics.com

Oxford Economics

4 Millbank, London SW1P 3JA, UK

Tel: +44 203 910 8061