HL Savings & Resilience Barometer – September 2025

Foreword

Richard Flint, Interim CEO, Hargreaves Lansdown

The HL Savings and Resilience Barometer reveals both the scale of the opportunity and the challenges we face as a nation when it comes to savings and investment. We see a growing retail investment culture in Britain, with investor numbers up, and innovative changes from the Government and regulators should see this flourish even further in the coming year. Financial resilience has also improved and readiness for retirement is now well above pre-pandemic levels.

However, the data shows there remains much more to do. Almost four million British households have the resources to invest but are not currently doing so – missing out on the opportunity to grow their wealth and take control of their financial futures. As we continue to improve and simplify our services, HL is committed to leading the way in helping the UK save and invest for a safer and more secure future.

The pandemic created a trend for investing which has sustained, starting with more time at home, and fewer things to spend money on, leaving them able engage with investment at a scale not seen before in the UK. We’ve seen this trend at HL too, with our client base increasing by more than 63% since the pandemic, as more and more Brits take control of their financial futures.

Creating and growing a retail investment culture in Britain has been at the core of HL’s purpose for over 40 years. Recent groundbreaking changes from the government and FCA to boost confidence and understanding should see this culture flourish further. Changes to the advice-guidance boundary will open up opportunities for more targeted support, increasing awareness and confidence in investing; and supporting innovation with more balanced risk warnings will better reflect the opportunities as well as the risks of investment.

This report gives more detail on how different demographic groups are investing as well as challenging assumptions about who invests. While 69% of households in the highest income quintile are investors, nearly a third (31%) are not. And even in the lowest income quintile, 760,000 households have the capacity to invest but are not doing so. As the City Minister recently said, “For too many their money is not working hard enough, and for too long advice on investments has been the preserve of only the wealthiest in society. To address this, the Chancellor has announced the biggest reform of the financial advice and guidance landscape in more than a decade.” The Barometer shows investing isn’t just for the rich. In fact, younger, lower-income, and single households have seen the largest increases in investment participation since the pandemic, driven in part by the rise of new asset classes like crypto.

If we are serious about creating an investing culture in the UK, we need to get serious about how we measure it. The current data landscape is fragmented and inconsistent, making it difficult to track progress or identify where support is most needed. We believe a more robust and consistent approach to measuring retail investing is essential if we want to build a nation of confident investors. There is an opportunity to convene ONS, FCA and industry to create a unified approach – combining survey data and actual client data – to better understand how the nation is investing.

This year’s Barometer also introduces a new methodology for assessing pension adequacy, and the results are eye-opening. By shifting to a benchmark based on the Target Replacement Rate and Living Wage, we’ve been able to explore pension resilience in far greater detail. Perhaps most surprising is the finding that higher-income households are struggling more than many might expect. While they may earn more today, many are not on track to maintain their standard of living in retirement –highlighting that income alone is not a guarantee of financial security. This is crucial as the second phase of the Government’s pension review begins and the way adequacy is assessed will dictate the policy approach and output of the work.

I’d like to thank Oxford Economics for their diligent and thoughtful approach to incorporating the latest Wealth and Assets Survey data, especially in light of the challenges surrounding its official status. They have also adopted further methodological tweaks as we learn from peers in the industry and challenge our thinking to refine the approach. The work of Oxford Economics ensures that the Barometer remains a robust and credible tool for understanding household finances.

Finally, I want to extend my sincere thanks to the members of our Sounding Board1. Their insights and challenge have been invaluable in shaping this report and ensuring it remains focused on the issues that matter most.

Financial resilience — the current state of the nation

The overall financial resilience score for Great Britain sat at 59.3 in 2025 Q2, remaining stable over the past year with a modest 0.1-point increase on its 2024 Q2 level. The stabilisation in the score suggests that, following a period of turmoil at the start of the decade, financial resilience in Great Britain has settled above its pre-pandemic level (56.2) but below its pandemic peak (60.9).

Fig. 1. How national financial resilience has changed from pre-pandemic2 to 2025 Q2

The limited change in the overall financial resilience score over the last 12 months reflects a more stable macroeconomic environment over this period. Household disposable income has increased by 1.6% in real terms. The savings rate has increased slightly from 9.1% in 2024 Q2 to 9.6% in 2025 Q2. The temporary increase in the rate seen in 2024 Q4, due to a spike in wages and government transfers, has unwound.

Fig. 2. The improvement in real household disposable income has slowed over the last 12 months, but the savings ratio continues to be relatively high compared to 2019 levels3

The “Save a penny for a rainy day” score, which has increased by 7.3 points compared to the pre-pandemic period, has seen the largest gains across the five pillars of financial resilience. This improvement has been driven by increases in the “Adequacy of liquid assets” and “Surplus income” indicators. On average, 52.1% of households currently have an adequate level of liquid assets, 4compared to the pre-pandemic proportion of 47.5%. However, the median household is expected to be saving―surplus income―£155 per month, over twice the pre-pandemic level of £62 per month.

There have also been gains in the “Control your debt” pillar, which has increased by 2.8 points compared to the pre-pandemic period. This improvement is driven by a reduction in the number of households with debt and a shift by many households to fixed-rate mortgages. These changes have strengthened the “Affordability of future debt repayments” and “Uncertainty of future debt repayments” indicators, which have risen by 2.4 and 8.5 points, respectively, and contributed to a 1.6-point improvement in the “Subjective evaluation of debt” position.

For the first time, the “Use of debt” indicator has been extrapolated using data from the eighth round of the Wealth and Asset Survey (WAS). The analysis shows an increase in the share of “good” debt, primarily due to lower overall debt levels, leading to a 2.2-point rise in this indicator.

The only indicator to decline within this pillar is “Arrears”, as the proportion of households in arrears is estimated to have increased from 7.4% to 8.9%. This increase has primarily been in the two lowest household income quintiles, with minimal change among the higher income groups. The proportion of households in arrears in the lowest income quintile rose from 21.9% to 27.0%, while the second quintile increased from 12.0% to 17.0%.

Fig. 3. Change in Barometer and pillar scores since the pre-pandemic

Financial resilience varies significantly across and within the regions of Great Britain. As depicted in the heatmap below the local authorities with the highest scores are generally spread throughout the “home counties” surrounding London. These local authorities tend to have homeownership rates and household incomes that are significantly above the national average.

Fig. 4. Variation in the Barometer score across the local authorities of Great Britain in 2025 Q2

See how resilient your area is

London has particularly low levels of financial resilience, with five of the 10 least resilient local authorities located in the capital, but eight of the 10 most resilient local authorities are in close proximity to London. The Barometer score for Elmbridge―the highest scoring local authority―is 15.0 points higher than the score in Kingston Upon Hull―the lowest scoring local authority. The average surplus income across local authorities in the top 10 is £341, which is £274 higher than the average for the bottom 10. The home ownership rate in the top 10 is also significantly higher at 70.6% compared to 43.2% in the bottom 10.

Fig. 5. Top and bottom ranking local authorities by Barometer score, 2024 Q4

| Top Ranking | LAD | Overall Index | Bottom Ranking | LAD | Overall Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Elmbridge | 67.3 | 354 | City Of Kingston Upon Hull | 52.3 |

| 2 | Hart | 66.0 | 355 | Newham | 52.6 |

| 3 | Epsom and Ewell | 65.9 | 356 | Barking and Dagenham | 52.6 |

| 4 | East Renfrewshire | 65.9 | 357 | Hackney | 52.8 |

| 5 | Wokingham | 65.8 | 358 | Nottingham | 52.9 |

| 6 | Waverley | 65.8 | 359 | Middlesbrough | 53.8 |

| 7 | St Albans | 65.5 | 360 | Leicester | 54.0 |

| 8 | Sevenoaks | 65.5 | 361 | Brent | 54.1 |

| 9 | Surrey Heath | 65.3 | 362 | Blackpool | 54.5 |

| 10 | East Dunbartonshire | 65.2 | 363 | Tower Hamlets | 54.6 |

The figures in this report reflect the recently published eighth round of the WAS – which details the financial position of households over the April 2020 to March 2022 period. In June 2025, the Office for Statistics Regulation (OSR) suspended the official status of the survey, citing issues such as its accuracy in representing different population demographics, particularly at more granular levels. As part of the integration exercise, Oxford Economics has taken a range of steps to rectify these issues using alternative data sources (boxes throughout the report provide further detail on this process). This approach ensures that valuable WAS data (particularly at the aggregate level) are reflected within the Barometer, while adjusting for the identified issues.

Box 1: Updating the household weights

The weights in the Barometer have been updated to reflect the 2021 England and Wales Census and the 2022 Scottish Census.

Within the Barometer, the household weights are underpinned by the weights from Round seven of the Wealth and Assets Survey (WAS). These weights have been updated to align with the demographic proportions reflected in Round 8, which are based on the latest census data. However, where we have observed divergences from the census data and where it is important for the Barometer modelling, we have used demographic proportions from the census instead. In particular, we have relied on census data for social and private renters as well as family composition, as the Round 7 and Round 8 weights have diverged from the census figures.

- Tenure: based on Round 8 of the WAS, social renters represent 15.7% of households, while private renters represent 21.9% of households. This differs from the census data, which shows 17.8% of households as social renters and 19.6% as private renters.

- Family composition: significant differences were identified for couples living on their own and those over 65. Based on the census data, 29.0% of households are couples living on their own, while in the WAS, this was 21.3%. In addition, the census data indicate that 22.2% of households are above 66, but in the WAS, this figure is 30.0%.

Key differences between Round 8 and the Census

Tenure

Round 8 WAS

Census

Homeowner outright

33.0%

31.1%

Homeowner with mortgage

29.3%

29.4%

Social renter

15.7%

17.8%

Private renter

21.9%

19.6%

Family composition

Round 8 WAS

Census

Single living on their own

20.5%

22.9%

Single with children

5.8%

7.0%

Couple living on their own

21.4%

29.4%

Couple with children

22.3%

18.8%

Over 66

30.0%

22.0%

| Tenure | Round 8 WAS | Census |

|---|---|---|

| Homeowner outright | 33.0% | 31.1% |

| Homeowner with mortgage | 29.3% | 29.4% |

| Social renter | 15.7% | 17.8% |

| Private renter | 21.9% | 19.6% |

| Family composition | Round 8 WAS | Census |

|---|---|---|

| Single living on their own | 20.5% | 22.9% |

| Single with children | 5.8% | 7.0% |

| Couple living on their own | 21.4% | 29.4% |

| Couple with children | 22.3% | 18.8% |

| Over 66 | 30.0% | 22.0% |

Oxford Economics’ approach to adjusting the weights in the dataset that underpin the Barometer improves the accuracy and representativeness of the estimates.

Financial resilience in key areas

Role of saving and investment

Saving plays an important role in determining households’ financial resilience. Within the Barometer framework, liquid assets serve as a vital buffer to protect against unforeseen events, such as sudden income loss. It is well established that having three months of essential spending as a cushion can help households weather economic challenges without resorting to debt or drastic reductions in their standard of living.5

Beyond this essential safety net, household assets can also be put to work through investing. By generating returns over time, investments help households grow their wealth and make the most of their money. This, in turn, supports longer-term financial goals–whether that means preparing for retirement, purchasing a home, or providing for children’s futures.

The following section will first investigate the coverage of liquid assets across Great Britain, identifying those who are failing to reach this savings minimum threshold. It will then explore who is investing, and the extent to which certain households could be making more of their savings.

In recent years, household wealth has shifted significantly, marked by a substantial rise in liquid savings coverage.

Over the Covid-19 pandemic, the combination of spending restrictions and government support measures led to an unprecedented accumulation of assets across many households. Indeed, the figure below shows that in 2025 Q2, the median household had 3.3 months of essential spending covered by their liquid assets. This is nearly a month more than the level of coverage seen pre-pandemic (2.6 months). Notably, some of this excess was used up to cope with rising prices during the cost-of-living crisis, but since then, the household savings rate has rebounded, leading to a steady increase in liquid asset accumulation.

Fig. 6. Savings compared to essential spending remain elevated, even after the cost-of-living crisis

The number of months of essential spending covered by liquid assets varies significantly across household groups.

- Households in the highest income quintile have 7.8 months of essential spending cover, compared to just 0.5 months for those in the lowest income quintile.

- Among employment types, the self-employed and employees hold similar levels of liquid asset adequacy (around 4 months), while non-working households have almost no coverage, averaging just 0.2 months.

- Across family types, couples without children typically have much higher coverage (over 7 months) compared to couples with children (2.3 months), reflecting the additional strain of dependents on household finances. Single parents and single-person households also have notably less liquidity to draw on during emergencies.

While there has been a general improvement in the adequacy of liquid assets indicator, this has been more pronounced among those with initially higher coverage. This shows how wealthier and more financially secure households were better positioned to build up liquid assets during the pandemic. These growing gaps highlight rising inequality and the persistent challenges the poorest households face in building even a modest level of financial resilience.

In addition, Fig. 7 highlights that there are many households with more than three months of essential spending covered by liquid assets. For these households, there is an opportunity to invest savings to improve their financial future; the composition of these households is explored in more detail in the following sections.

Fig. 7. The gap between the wealthiest and poorer households has increased

Box 2: Estimating the change in investors

The Barometer dataset has been adjusted to reflect trends in the number of new investors from the Financial Lives Survey (FLS)

The latest Wealth and Assets Survey (WAS) does not show an increase in the proportion of households investing between Round 7 (April 2018 to March 2020) and Round 8 (April 2020 to March 2022). This stands in contrast with findings from the Financial Lives Survey (FLS) and data from Hargreaves Lansdown.

The FLS found that the there was a 5-percentage point increase in the number of adults who were investing between the 2020 and 2022 surveys, rising from 32% to 37%. Furthermore, data from Hargreaves Lansdown show that they had 281,000 more clients in investing accounts (excluding cash and pensions) in March 2022 compared to April 2020, a 28.1% increase, bringing their total active client base to 1.9 million as of September 2024.

Given this, the change in investors in the Barometer continues to be underpinned by the FLS. Based on the FLS, the proportion of households classified as investors in the Barometer dataset rose by 3.7 percentage points between the pre-pandemic period and 2022 Q1. Interestingly, the analysis shows that the increase in investors is strongly linked to a higher proportion of younger, lower-income and single adults becoming investors. See the Methodology Report for more details on this analysis and conversion to the household level.

Change in the proportion of investors, 2202 Q1 vs pre-pamdemic (income, age and relationship status)

While several factors may contribute to the divergence between the surveys, one likely explanation is that the FLS asks questions on a wider range of asset categories than the WAS. Over time, the FLS has expanded to include newer investment products, whereas these are typically grouped under a broad “other investments” category in the WAS. This could mean that respondents to the WAS do not consider these less traditional asset categories when responding to the other investments question, leading to an underestimation of investors. According to the 2022 FLS data, 9.2% of adults surveyed held at least one of these newer types of investment accounts*.

New asset categories added to the Financial Lives Survey over time

| Asset/Products | Year of introduction |

|---|---|

| Cryptocurrencies or crypto assets | 2020 |

| Peer-to-peer lending | 2020 |

| Investment-based crowdfunding | 2020 |

| Contract for Difference (CFD) | 2022 |

| Mini bonds | 2022 |

There has been an increase in the number of households investing, with significant differences in the proportion investing across household cohorts

Within the Barometer, households are identified as being investors if they hold less liquid assets.6 By 2022, the proportion of households in this category had increased by 3.7 percentage points (ppts) relative to the pre-pandemic level (see Box 3 for more details). Fig. 8 illustrates clear differences in investment participation across different household groups. As expected, it shows that higher-income individuals are more likely to invest, where 63.0% of those in the top income quintile invest, compared to 23.2% of the lowest. Those in couples, who can split living costs across two incomes, are also more likely to be investors, with 47.7% of couples investing compared to 32.4% of single households.

Fig. 8. Wealthiest and those in a couple are more likely to be investors

An in-depth examination of investment participation rates among single/coupled households shows a range of interesting trends.

The likelihood of a couple being an investor increases with age, with 42.8% of couples in the 20–40 age group investing, compared to 57.7% of couples over 55. However, for single households, age has little impact on the rate of households investing with 32.2% of single households in the 20-40 age group investing and 33.2% of single households in the over 55 age group investing. This is despite older households typically having larger surplus incomes.

The proportion of female investors is lower than the proportion of male investors across both single and coupled households. Only 27.6% of single females are investors, compared to 38.6% of single males. Meanwhile, in coupled households, 9.8% had only a female partner investing, compared to 15.2% where only a male partner was an investor. In 22.7% of households, both individuals were investors.

Fig. 9. Females tend to invest less than their male counterparts7

Many households are underinvesting, while some should not be investing at all

Within the Barometer framework, we have defined households that should not be investing as those households that meet at least one of these criteria:

Worryingly, our analysis indicates that 27.9% of households–representing 2.9 million–who meet one or more of these conditions are nevertheless investing. This raises concerns, as these households may be better served by prioritising debt repayment and building their short-term financial resilience before committing funds to investments.8

At the same time, there is a significant group of households that appear to be underutilising their financial potential. Across Great Britain, there are 8.8 million households that have excess liquid savings, are not in arrears, and do not feel that debt is a burden. Of this group, 58.5% of these households are already investing, but 41.5% are not. Both sets of households can improve their financial position by reallocating excess liquid assets into investments.

The Barometer also reveals important trends across income levels. The highest-income quintile contains the largest number of households with the capacity to invest more–3.2 million in total. However, even in this group, nearly a third (31%) are not currently investing. This is surprising given their high earnings and excess cash. Even in the lowest income quintile, there are still 760,000 households that could improve their financial position by reallocating excess liquid assets into investments, demonstrating that underinvestment is not confined to higher-earning households.

Fig. 10. Many households could invest or move more money into investment assets

Many people who have the financial capacity to invest may still choose not to, and this can be due to a range of factors, such as saving for a house deposit, getting married, or the type of employment they are in. Some of these goals often require substantial liquid savings, which can make individuals hesitant to tie up money in longer-term investments. Younger households (aged 20–40) have the highest proportion of non-investors (45.0%), which could reflect their focus on near-term financial milestones, like homeownership or starting a family. When looking at employment status, self-employed households have the lowest proportion of non-investors (38.8%), likely because they are more reliant on non-pension assets to fund their retirement–a topic explored in more detail in the next section.

Fig. 11. The proportion of non-investing households differ by age and employment

Adequacy in pension savings

In the latest edition of the Barometer, the pension adequacy benchmark has been updated. It has changed from the Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association’s (PLSA) moderate standard of living in retirement. The new benchmark is an adjusted version9 of the Pension Commission’s Target Replacement Rate (TRR) with a floor derived from the Living Wage Pension. This new benchmark better assesses households’ ability to smoothly transition into retirement without compromising their standard of living, while ensuring a minimum income sufficient to meet basic needs in retirement. Our Pension Adequacy Report published in June 2025 provide further detail.

Using this new methodology, the proportion of households achieving pension adequacy increases by 15.8 percentage points, relative to its previous level. This reflects the fact that households perform better when targeting a proportion of their expected income in retirement rather than a threshold based around the PLSA’s moderate standard of living.

There has been an increase of 1.7 percentage points in households with adequate pensions based on the new threshold, as growth in pension pots has outpaced the threshold. In contrast, there is a decline in the PLSA moderate measure. This is primarily due to methodological changes introduced in 2023, causing a large increase in the pension income required to meet the moderate standard of living.10

Despite the lower adequacy bar set by the new measure and an improvement in the proportion, only 43% of households have adequate pension savings. This indicates that most households are still unlikely to maintain their living standards or reach a minimum income threshold in retirement.

Fig. 12. The pension value indicator is now based on the Target Replacement Rate (TRR) and Living Wage (LW)

Box 3: Estimating the change in pension values

The Barometer has been updated to reflect improvements in the measurement of defined benefit (DB) pension values.

The change in approach for calculating pension value affects the pension indicator across all periods–historical, current, and forecast–as we have used the available data in Round 8 of the WAS to re-align the historical DB pension values from Round 7.

The key methodological update is that the WAS now estimates the current value of future pension promises, both before and after retirement, using the Superannuation Contributions Adjusted for Past Experience (SCAPE) discount rate. This replaces the previous use of market-based discount rates, resulting in a more consistent and policy-relevant valuation of DB pensions.

The new metric shifts the picture on adequacy across the income and tenure spectrum

The new benchmark–based on an adjusted version Pension Commission’s Target Replacement Rate (TRR) with a floor derived from the Living Wage Pension–see less variation in pension adequacy performance across the income quintiles. Under the old approach only 5.9% of households in the bottom quintile achieved pension adequacy, compared to 51.8% in the top quintile. Under the new approach, pension adequacy is around 40% across each income quintile. This reflects the expectation that the state pension and housing benefits will closely align with the income required by the poorest, and the fact that the wealthiest require a substantial pension to maintain their living standards in retirement.

Differences are also evident across tenure types with 64.2% of homeowners achieving adequacy under the new metric, compared to only 31.7% of renters. This variation is driven by homeowners typically needing less income in retirement as they do not face rental costs. This makes it easier for them to meet the pension adequacy benchmark, whereas renters must accumulate substantially more savings to achieve a comparable level of financial security.

Fig. 13. Once living standards are accounted for, there is limited differences in adequacy levels between income groups, but more variation across tenure

The pension gap is largest for the wealthiest households

The pension gap11 for these households is calculated to illustrate how much additional savings would be needed to meet the benchmark. As shown in Fig. 14, although there is an even distribution of households reaching the adequacy threshold, the median pension gap is largest among the highest-earning households. The median household in the top income quintile has a pension adequacy gap of £64,750, reflecting the larger pension pot they require to maintain their current living standards.

Fig. 14. Households with the highest living standards tend to have the largest pension gaps

The revision of the pension adequacy benchmark has resulted in changes at the regional level

At the local authority level, the variation in pension adequacy is now more closely linked to housing tenure. Areas with large populations of renters tend to perform worse, with cities and urban areas particularly affected. London stands out as performing especially poorly, as it has many high earners who are less likely to be able to replace their pre-retirement incomes, along with a high proportion of renters who are more likely to fall below the Living Wage floor set by the new measure. This contrasts with results under the previous approach using the PLSA benchmark, which were more closely aligned with household income. Under that measure, areas with lower average incomes, such as Wales and Scotland, tended to fare worse.

Fig. 15. Variation in the proportion of households to have achieved resilience in “Pension value” across the local authorities of Great Britain in 2025 Q2

The average proportion of households achieving pension adequacy in the 10 best-performing local authorities is 26.7 percentage points higher than in the 10 lowest-scoring areas

In the top 10 local authorities, 54.1% of households meet the benchmark, compared to just 27.5% in the lowest-ranked local authorities, a 26.7 percentage point difference. In Craven–the highest-scoring local authority–the median household has a positive pension gap12 of £8,154, in stark contrast to Islington, where the median gap reaches -£26,981. On average, households in the top 10 local authorities have a positive pension gap of £4,767, compared to a gap of -£29,787 for those in the 10 lowest-scoring local authorities.

Fig. 16. Top and bottom ranking local authorities proportion of households to have achieved resilience in “Pension value”, 2025 Q213

| Top Ranking | LAD | % of households to have achieved resilience threshold | Pension gap | Bottom Ranking | LAD | % of households to have achieved resilience threshold | Pension gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Craven | 56.1 | 8,154 | 354 | Hammersmith And Fulham | 29.3 | -26,098 |

| 2 | South Hams | 55.8 | 12,190 | 355 | Lambeth | 28.7 | -18,453 |

| 3 | Eden | 55.3 | 10,972 | 356 | Greenwich | 28.5 | -21,506 |

| 4 | West Devon | 54.8 | 4,229 | 357 | Tower Hamlets | 28.3 | -18,283 |

| 5 | York | 53.5 | 1,873 | 358 | City Of London | 27.9 | -42,995 |

| 6 | Ryedale | 53.2 | 1,080 | 359 | Camden | 27.8 | -24,677 |

| 7 | Powys | 53.2 | 134 | 360 | Southwark | 26.6 | -32,936 |

| 8 | East Lothian | 53.1 | 6,857 | 361 | Westminster | 26.3 | -40,051 |

| 9 | Flintshire | 53.1 | 1,162 | 362 | Kensington And Chelsea | 25.7 | -45,885 |

| 10 | Pembrokeshire | 53.0 | 1,024 | 363 | Islington | 25.5 | -26,981 |

Box 4: Incorporating house price and rental data

New house price and rental data have been incorporated into the Barometer, improving the robustness of key indicators.

House prices play a key role in the Barometer, particularly in underpinning the Homeownership in Retirement indicator. However, due to sampling challenges, the ONS has indicated that property wealth data in the latest Wealth and Assets Survey (WAS) are not robust, particularly at the regional level. Additionally, we anticipate that households may struggle to accurately report the current value of their home, accounting for recent changes in local housing markets. As a result, we have continued to use local authority-level house price data published by the Land Registry to estimate property values within the Barometer.

New rental data have also been incorporated into the Barometer dataset. When compared to ONS-published figures, the rental values reported in the WAS are approximately 17% lower. To address this, we have adjusted the WAS rental data to align with ONS figures at a regional level. This adjustment affects estimates of household essential spending and, in turn, influences several key indicators–specifically, Adequacy of Liquid Assets, Surplus Income, and Net Financial Assets.

Households can use non-pension assets to help finance their retirement

Just over two in five households (42.0%) report holding some form of non-pension investment or a pension pot. Specifically, 38.1% of households have a pension and investments, while another 3.9% have no pension but investments. A further 43.7% of households report having a pension but no additional investments. While 14.3% of households have neither a pension nor investments, leaving them particularly exposed to income shortfalls later in life.

Fig. 17. Many households hold multiple financial assets that could finance their retirement

When these investment assets are combined with liquid assets above three months of essential spending, the overall picture of pension adequacy improves, resulting in an 8.5-percentage point increase in the proportion of households meeting the adequacy threshold. The self-employed–who typically have much lower adequacy scores compared to employed households–experience the largest gains (10.7 percentage points) when these additional assets are factored into our pension adequacy assessment. As discussed in a previous report, self-employed individuals rely on a wider range of financial assets to support their retirement given their limited access to workplace pensions.14

Fig. 18. Non-pension assets increase the number of households achieving pension adequacy with the self-employed seeing the largest gains

Life insurance

The Barometer’s life insurance indicator measures the proportion of households with dependents whose liabilities exceed the combined value of their assets and life insurance policies. According to data from the WAS, the share of households with life insurance has increased by 2.0 percentage points, rising from 18.3% to 20.3%. This, together with the asset growth seen over the pandemic, has led to an improvement in the indicator from a pre-pandemic level of 46.0% to 49.9%.

Despite this progress, the challenge remains significant: of the 14 million households with dependents across Great Britain, around 7 million still lack sufficient life insurance and assets to cover a catastrophic shock. Households with children fare worse than those without, as they often do not adequately account for the additional costs of raising a child to age 18. Homeowners with a mortgage also score lower on this indicator, since their outstanding mortgage debt represents a liability that renters and outright homeowners do not carry.

Coverage is lowest among renters with children–only 16.6% have adequate assets and insurance to cover both their liabilities and the cost of raising a child. By comparison, renters without children perform much better, with 78.7% achieving adequacy. Homeowners with both children and a mortgage fall just below the national average (48.4%), as they need higher levels of coverage to meet their financial obligations. In contrast, outright homeowners without children have the highest adequacy rate, at 95.4%, as they generally only need enough coverage to meet any remaining non-mortgage liabilities.

Fig. 19. There is a significant difference between coverage based on family type and tenure

Outlook for the next 12 months

The outlook for household financial resilience in 2026 remains broadly stable, supported by steady trends in disposable income and the continuation of elevated saving rates. Real disposable household income is projected to increase by 1.2% between Q2 2025 and Q2 2026. Although inflation is expected to ease toward the target rate, wage growth is also anticipated to slow, which will limit the real gains in income.

Fig. 20. Savings are expected to remain elevated, while real disposable income growth is anticipated to be unchanged

The continuation of elevated savings will continue to mean the financial resilience remains above its pre-pandemic level

The “Save a penny for a rainy day” pillar is expected to improve slightly, with the score rising by 0.4 points between Q2 2025 and Q2 2026. Median household surplus income is projected to remain relatively stable at around £143 in Q2 2026, compared with £155 in Q2 2025. Similarly, households are expected to hold approximately 3.5 months’ worth of liquid assets, slightly higher than the 3.3 months recorded in Q2 2025.

The “Plan for later life” pillar is forecast to see a modest decline of 0.2 points over the same period. This is primarily driven by a 0.9-point decrease in the “Homeownership” indicator. The decline reflects house prices rising more slowly than inflation, resulting in a real reduction in house prices. Between Q2 2025 and Q2 2026, house prices are anticipated to increase by 1.3%, compared to a CPI rate of 2.1%.

Within this pillar, the “Value of pension” indicator is expected to remain broadly stable. In Q2 2026, 42.4% of households are projected to reach the pension adequacy threshold, a figure similar to the 43.0% reported in Q2 2025. However, the pension gap is anticipated to widen, increasing to £4,813 in Q2 2026 from £4,271 in Q2 2025.

Fig. 21. Overall financial resilience is expected to remain elevated

Over the next 12 months, our baseline forecast assumes the Bank of England’s base rate will decline to 3.25 ppts, and that there is share price growth of 6.3%. However, in an alternative scenario, financial markets weaken as valuations adjust to heightened economic uncertainty, increased near-term inflationary pressures, and growing concerns about Federal Reserve independence and the credibility of US policy. In this scenario, the stock market is projected to decline by 5.2%, while interest rates are expected to fall further to 2.75 ppts.

Fig. 22. Lower interest rates and faster economic growth boost house prices and the financial markets

In the scenario, older households are less affected because these households tend to be less exposed to stock market fluctuations in their pension portfolios. This is partly because they hold a greater share of government bonds, which offer more stable and, in some cases, higher returns through a downturn. Additionally, a larger portion of their pension wealth is tied up in pension schemes that are not directly linked to stock market performance.

Fig. 23. A fall in the stock market has a larger impact on younger households

About the barometer

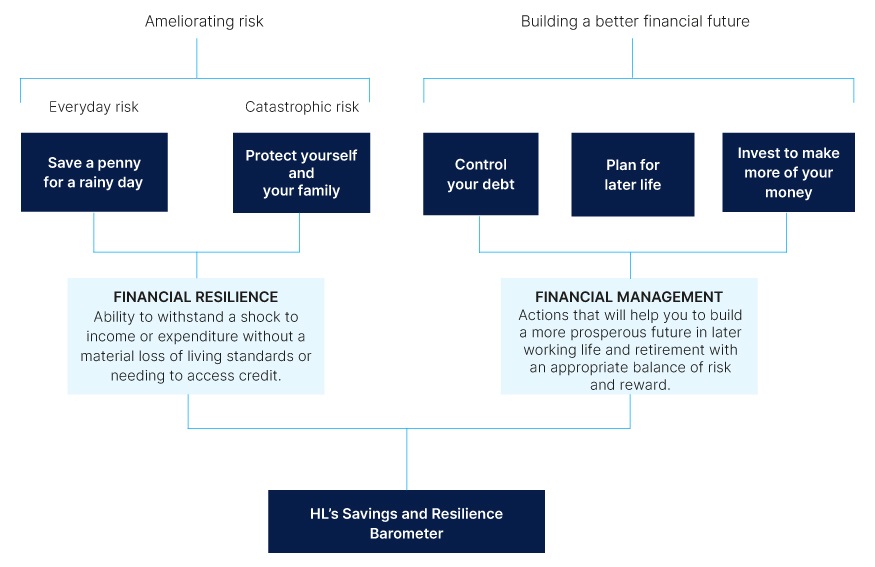

The Savings and Financial Resilience Barometer is an index measure designed and produced by Oxford Economics. It is based around Hargreaves Lansdown’s five building blocks for financial resilience depicted below. The aim of the barometer is to provide a holistic measure of the state of the nation’s finances, monitoring to what extent households are prudently balancing current and future demands, while also guarding against alternative types of risk.

Fig. 24. Savings and Resilience Barometer: conceptual structure

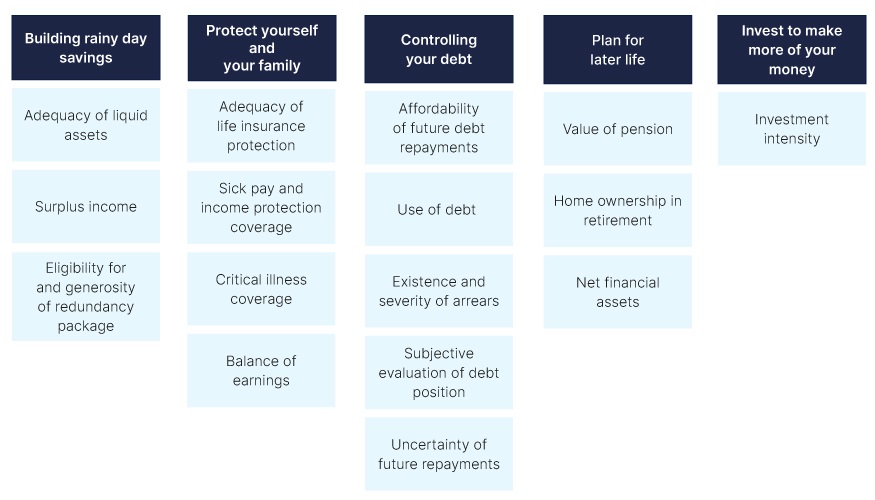

In collaboration with Hargreaves Lansdown, Oxford Economics has mapped each of these pillars to a list of 16 individual indicators. The data underpinning the indicators were sourced from a household panel dataset for a representative group of British households developed by linking together official datasets. The Round 7 of the Wealth and Assets Survey (WAS), published by the ONS, was used as the core dataset due to the breadth of financial data available in the survey. This source does not include every variable required to measure the factors. Therefore, we have used a range of methods, including econometric analysis, to build upon the core dataset using data from the Financial Lives Survey (FLS), Living Costs and Food Survey (LCFS), and the Labour Force Survey (LFS).

For each indicator, the data were used to create an index value on a scale of between zero and 100 for households in the panel. In each case, a score of 100 was assigned to households who had reached a specified resilience threshold, e.g., holding liquid assets equivalent to at least three months of essential expenditure. Households whose savings could cover more than three months of spending were, therefore, not rewarded for this additional level of security. Such a design is appropriate to capture the concept of resilience, and the intrinsic trade-offs involved in financial management. Threshold values were defined with reference to benchmark recommendations where available and, where not, were specified using the statistical distribution of values within the dataset and the judgement of the research working group.

Fig. 25. Savings and Resilience Barometer: Barometer Indicators

To bring the dataset up to date, values were extrapolated through to 2024 Q4 using a wide range of macroeconomic and survey data, as well as different modelling techniques. In addition, the July 2025 release incorporates data from Round 8 of the WAS. A much more detailed description of the approach can be found in the methodology report available on the project’s landing page.15 Finally, current and future values are projected based on Oxford Economics’ baseline forecast for the UK economy from its Global Economic Model (GEM).

Methodology changes

For the July 2025 release, there have been two significant enhancements to the Barometer framework.

- Firstly, the framework has been updated to incorporate the latest findings from Round 8 of the WAS; and,

- Secondly, the dataset structure has been updated to enable more accurate Local Authority District (LAD) trends to be included.

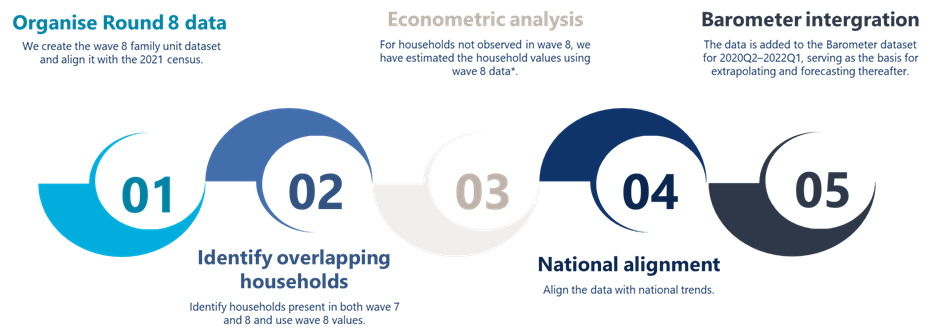

Our approach to incorporating Round 8 of the Wealth and Asset Survey into the Barometer consisted of five key steps:

In June 2025, the Office for Statistics Regulation (OSR) suspended the official status of the eight round of the WAS, citing issues such as its accuracy in representing different population demographics, particularly at more granular levels. As part of the integration exercise, Oxford Economics has undertaken a range of steps to rectify the issues using alternative data sources, such as the household weights, number of new investors, along with house and rental prices. In addition, we have made several updates to the pension indicator.

Household weights

The Barometer’s household weights have been updated to incorporate the latest data from the 2021 England and Wales Census and the 2022 Scottish Census. In the Barometer, household weights are initially derived from Round 7 of the Wealth and Assets Survey (WAS). These have since been revised to match the demographic distributions observed in Round 8, which reflect the most recent census data.

Where significant discrepancies with census data have been identified, and where these differences are important to the Barometer’s modelling, we have instead applied census demographic proportions. In particular, census figures were used to improve the representation of social and private renters, as well as household composition, where the Round 7 and Round 8 WAS weights differed notably from the census benchmarks.

Number of investors

The Barometer dataset has been updated to more capture the rise in new investors highlighted by the Financial Lives Survey (FLS). Unlike the WAS, which showed a fall in the proportion of households investing between Round 7 (April 2018–March 2020) and Round 8 (April 2020–March 2022), the FLS and figures from Hargreaves Lansdown point to a marked increase.

FLS data indicate that the share of adults holding investments grew by 5 percentage points over this period, rising from 32% to 37%. Meanwhile, Hargreaves Lansdown added 483,000 new clients to investment accounts (excluding cash and pensions), expanding their total client base to 1.9 million by March 2022.

Given this supporting evidence, the Barometer’s assessment of investor growth continues to be anchored in the FLS results. Overall, the share of households identified as investors in the Barometer increased by 3.7 percentage points between the pre-pandemic baseline and the first quarter of 2022.

Housing and rental prices

House prices are an important input in the “Homeownership in retirement” indicator. However, the ONS has highlighted sampling limitations in the most recent WAS property wealth estimates, especially at the regional level.16 Additionally, it is likely that households may not accurately report the current market value of their homes, given recent volatility in local housing markets. To improve reliability, we have continued to use Land Registry data at the local authority level to estimate property values within the Barometer.

Updated rental market data have also been incorporated. Comparisons with ONS data revealed that WAS rental values were about 17% lower than official estimates. To correct for this discrepancy, we adjusted the WAS rental figures to align with ONS government office regional. In addition, Local Authority District (LAD) rental prices have been added to the LAD weight estimation, helping to align the average rental prices of the households in the Barometer dataset with those seen in the Local Authority.

Pension indicator

There have been two significant updates to the pension indicator. Firstly, the Barometer has incorporated enhancements to the approach for valuing defined benefit (DB) pensions, which affect all periods of the Barometer.

A key methodological shift is that the WAS now uses the Superannuation Contributions Adjusted for Past Experience (SCAPE) discount rate to determine the present value of future pension promises, both pre- and post-retirement. This replaces the prior reliance on market-based discount rates and results in valuations that are more stable and relevant for policy purposes. As illustrated in Fig. 26, this has led to a fall in the median and mean pre-retirement DB pension wealth.

Fig. 26. Revisions to defined benefits in Great Britain, April 2018 to March 2020 (Round 7)17

| Methodology | Median pre-retirement DB pension wealth (£) | Mean pre-retirement DB pension wealth (£) |

|---|---|---|

| Published methodology | 71,700 | 194,600 |

| Updated methodology | 65,100 | 126,600 |

| Percentage (%) difference between two methodologies | -9 | -35 |

Previously, the Barometer used the Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association’s (PLSA) moderate standard of living in retirement as its benchmark. This has now been replaced with an adjusted version of the Pension Commission’s Target Replacement Rate (TRR)18, which sets retirement income targets relative to households’ pre-retirement earnings. To ensure a minimum standard, this approach is underpinned by a floor based on an adjusted version of the Living Wage pension, which reflects an income level sufficient to meet basic needs in retirement.19 The tables below show the 2019 and 2025 income required in retirement by benchmark.20

Fig. 27. PLSA income required by living standard

| Living standard | Single | Couple | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2025 | 2019 | 2025 | |

| Minimum | £10,200 | £15,800 | £15,700 | £24,600 |

| Moderate | £20,200 | £34,300 | £29,100 | £47,300 |

| Comfortable | £33,000 | £47,300 | £47,500 | £64,700 |

Fig. 28. Living wage pension required by tenure

| Living standard | Single | Couple | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2025 | 2019 | 2025 | |

| Homeowner | £10,470 | £14,620 | £16,160 | £22,580 |

| Social renter | £14,070 | £1,976 | £19,970 | £28,030 |

| Private renter | £16,000 | £2,219 | £22,450 | £31,150 |

Fig. 29. Original and updated target replacement rate

| Gross earnings band 2025 | Original TRR | Updated TRR |

|---|---|---|

| Less than £18,900 | 80% | 86% |

| £18,900 to £34,900 | 70% | 76% |

| £34,900 to £49,700 | 67% | 72% |

| £49,700 to £79,600 | 60% | 62% |

| Over £79,600 | 50% | 50% |

Updated data structure of the Barometer

The dataset structure has been updated so that each row now corresponds to an individual household within a specific LAD. Households for each LAD have been sampled from the wider Government Office Region (GOR) where the LAD is situated.

Household-specific weights within each LAD have been estimated, and the sum of these weights across all LADs matches the national totals, ensuring consistency between the national and local results.

Similar to the previous approach, the likelihood of each family residing in a specific local authority was calculated based on its wealth distribution and demographic composition. This was then combined with its national family weight to estimate a LAD-specific weight for each family.

This updated structure allows for a more precise reflection of LAD-specific trends in variables, such as rents and house prices. For instance, while house price growth was previously applied uniformly at the GOR level, it is now measured and applied at the more granular LAD level.

About Oxford Economics

Oxford Economics was founded in 1981 as a commercial venture with Oxford University’s business college to provide economic forecasting and modelling to UK companies and financial institutions expanding abroad. Since then, we have become one of the world’s foremost independent global advisory firms, providing reports, forecasts and analytical tools on more than 200 countries, 100 industries, and 7,000 cities and regions. Our best-in-class global economic and industry models and analytical tools give us an unparalleled ability to forecast external market trends and assess their economic, social and business impact.

Headquartered in Oxford, England, with regional centres in New York, London, Frankfurt, and Singapore, Oxford Economics has offices across the globe in Belfast, Boston, Cape Town, Chicago, Dubai, Dublin, Hong Kong, Los Angeles, Mexico City, Milan, Paris, Philadelphia, Stockholm, Sydney, Tokyo, and Toronto. We employ 450 staff, including more than 300 professional economists, industry experts, and business editors–one of the largest teams of macroeconomists and thought leadership specialists. Our global team is highly skilled in a full range of research techniques and thought leadership capabilities from econometric modelling, scenario framing, and economic impact analysis to market surveys, case studies, expert panels, and web analytics.

Oxford Economics is a key adviser to corporate, financial and government decision-makers and thought leaders. Our worldwide client base now comprises over 2,000 international organisations, including leading multinational companies and financial institutions; key government bodies and trade associations; and top universities, consultancies, and think tanks.

January 2025

All data shown in tables and charts are Oxford Economics’ own data, except where otherwise stated and cited in footnotes, and are copyright © Oxford Economics Ltd.

The modelling and results presented here are based on information provided by third parties, upon which Oxford Economics has relied in producing its report and forecasts in good faith. Any subsequent revision or update of those data will affect the assessments and projections shown.

To discuss the report further please contact:

Henry Worthington:hworthington@oxfordeconomics.com

Oxford Economics

4 Millbank, London SW1P 3JA, UK

Tel: +44 203 910 8061

1The Sounding Board includes representatives from DWP, HM Treasury, FCA, MaPS, Step Change, Nest Insight, Nationwide, Swiss Re, Blackrock, Great Western Credit Union as well as Professor Sharon Collard, Faith Reynolds and Johnny Timpson.

2Pre-pandemic data based on the seventh wave of the Wealth and Asset Survey (WAS) from 2018 Q2 to 2020 Q1.

3Savings ratios are calculated as household disposable income minus household consumption divided by household disposable income. This may differ from other measures of savings ratios, which can include non-household specific indicators.

4Sufficient liquid assets to cover three months of essential expenditure.

5According to the Money Advice Service, “[a] good rule of thumb to give yourself a solid financial cushion is to have three months’ essential outgoings available in an instant access savings account”.

6 See methodology document for a full list of less liquid assets.

7The change in the number of investors within the Barometer is modelled at the household level. To estimate the number of investors by gender within each household, we adjusted the investor counts identified in Round 7 of the WAS to align with the overall increase observed in the Financial Lives 2022 survey. Although the composition of investors within households may have shifted, the FLS shows that men remained more likely than women to be investors during the pandemic. Specifically, the FLS reports that 46% of males are investors compared with 29% of females, a difference consistent with our findings.

8It should be noted that some households may have started investing before experiencing one of these conditions, and this may be a temporary challenge. As such, it does not necessarily mean they should liquidate their investments when this happens.

9The rates used have been estimated by the Resolution Foundation and have been adjusted to reflect changes in the tax system since the original rates were set by the Pension Commission.

10In 2023, the PLSA’s estimate for a “moderate income in retirement” rose significantly beyond the rate of inflation due to methodological changes. Additional costs were included, such as financial support for family members and meals out with family.

11The pension gap is estimated as the difference between the household pension savings and the required savings to meet the needs based on the TRR and LW benchmarks.

12A positive pension gap means that the household has pension savings above the savings threshold needed to achieve pension adequacy.

13The pension gap metric is based on the size of the pension gap for the median household in each local authority. While local authorities with higher pension adequacy tend to have smaller (or positive) pension gaps, the metrics are different and the ranking would differ if pension performance was ranked by the pension gap in each area.

14For a deep dive on the self-employed financial resilience see Self-Employed Financial Resilience

15https://www.hl.co.uk/features/5-to-thrive/savings-and-resilience-comparison-tool

16https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/personalandhouseholdfinances/debt/methodologies/wealthandassetssurveyqmi

17ONS: Estimating defined benefit pension wealth in Great Britain: December 2024

18The rates used have been estimated by the Resolution Foundation and have been adjusted to reflect changes in the tax system since the original rates were set by the Pension Commission.

19The final Living Wage Pension used to calculate the required pension pot reflects housing subsidies, expected to be received by renters.

20Total wages and salaries are used to estimate 2025 figures for the PLSA and LW pension benchmarks, along with updating the bandings for the TRR.